|

xxxx |

The Havelis of Shekhavati:

a photo essay by Madhulika

Liddle

1)

The

Hindu god Krishna, recognisable by his blue-pigmented skin, holds hands

with adoring women as he cavorts around the rectangular edge of an ornately

painted ceiling in a haveli-- a mansion-- in Shekhavati. Shekhavati ('The

Garden of Shekha’) lies within the historic subdivision of Rajasthan known

as Marwar, and is named for a local medieval chieftain called Rao Shekha

(1433-88). It is a hot, arid land, its dusty profile relieved by scrub

brush-- and by splendid early-20th-century havelis. 1)

The

Hindu god Krishna, recognisable by his blue-pigmented skin, holds hands

with adoring women as he cavorts around the rectangular edge of an ornately

painted ceiling in a haveli-- a mansion-- in Shekhavati. Shekhavati ('The

Garden of Shekha’) lies within the historic subdivision of Rajasthan known

as Marwar, and is named for a local medieval chieftain called Rao Shekha

(1433-88). It is a hot, arid land, its dusty profile relieved by scrub

brush-- and by splendid early-20th-century havelis.

The havelis are to be found in a handful of towns and villages-- Mukandgarh,

Mandawa, Fatehpur, Nawalgarh, Dundlod, Jhunjhunu and Baggar-- and are lavishly

decorated with exquisite (and more often than not, quirky!) frescoes. Colonnaded

and adorned with wrought iron balconies, shuttered windows, and frescoes

depicting everything from European ladies and pink-cheeked cherubs to local

warriors and Hindu deities, the havelis are more than mere houses.

2)

The

havelis of Shekhavati, almost without exception, owe their existence to

local merchants who made it big. The Marwaris are universally acknowledged

to be canny businessmen, and in the 18th and 19th centuries a large number

of them headed for the metropolises (mainly Bombay and Calcutta) and swiftly

set about amassing fortunes. By the early 1900s, many of them had made

vast sums of money in industries as diverse as cotton and opium; and they

were ready to show off their wealth back home in Shekhavati. 2)

The

havelis of Shekhavati, almost without exception, owe their existence to

local merchants who made it big. The Marwaris are universally acknowledged

to be canny businessmen, and in the 18th and 19th centuries a large number

of them headed for the metropolises (mainly Bombay and Calcutta) and swiftly

set about amassing fortunes. By the early 1900s, many of them had made

vast sums of money in industries as diverse as cotton and opium; and they

were ready to show off their wealth back home in Shekhavati.

A number of these millionaires were philanthropists like Seth Chaturbhuj

Piramal Makharia, the man who made the Piramal haveli in Baggar. Piramal

constructed schools and hospitals, and donated great sums of money for

the welfare of Baggar’s residents. Baggar is today, thanks to the efforts

of the Piramal clan, a prosperous hamlet; and its best-known building is

the beautifully frescoed Piramal haveli. In the photograph shown here is

a portion of a fresco adorning the wall around the first courtyard of the

Piramal haveli. On the left is a typically Indian subject: Lakshmi, the

Hindu goddess of wealth, bestowing largesse on her devotees. On the right

is another deity straight out of Hindu scripture: Krishna playing his flute.

In the centre, incongruously enough, is a cherub.

3)

Another example of the delightfully eclectic style of Shekhavati art: East

and West meet on a single plane-- this time on a temple wall. The Gopinath

Mandir in Mukandgarh, otherwise none too spectacular, has large frescoes

on its walls; and as one would expect, the frescoes are predominantly of

characters out of Hindu mythology. The fresco depicted in the photograph

centres around the monkey-god, Hanuman, shown wrestling with another monkey.

The fascination with all things European, however, shows through-- the

faded figures below the main fresco are definitely sitting on Victorian

chairs. And one of the figures-- the one on the far right-- is obviously

wearing a hat. 3)

Another example of the delightfully eclectic style of Shekhavati art: East

and West meet on a single plane-- this time on a temple wall. The Gopinath

Mandir in Mukandgarh, otherwise none too spectacular, has large frescoes

on its walls; and as one would expect, the frescoes are predominantly of

characters out of Hindu mythology. The fresco depicted in the photograph

centres around the monkey-god, Hanuman, shown wrestling with another monkey.

The fascination with all things European, however, shows through-- the

faded figures below the main fresco are definitely sitting on Victorian

chairs. And one of the figures-- the one on the far right-- is obviously

wearing a hat.

4)

A short walk along a very dusty road from the Gopinath Mandir in Mukandgarh,

is the Saraf haveli. Like most of the havelis in Shekhavati, the Saraf

haveli too is no longer occupied by the clan that constructed it. (The

majority of Shekhavati’s havelis are occupied by caretakers who have now

become, more or less, de facto owners. Some havelis, long abandoned, have

been taken over by squatters, who scrawl over the frescoes, or allow smoke

from kitchen fires to blacken them.) 4)

A short walk along a very dusty road from the Gopinath Mandir in Mukandgarh,

is the Saraf haveli. Like most of the havelis in Shekhavati, the Saraf

haveli too is no longer occupied by the clan that constructed it. (The

majority of Shekhavati’s havelis are occupied by caretakers who have now

become, more or less, de facto owners. Some havelis, long abandoned, have

been taken over by squatters, who scrawl over the frescoes, or allow smoke

from kitchen fires to blacken them.)

The men and boys sitting outside the Saraf haveli are not occupants-- they

are just curious locals. The family no longer lives at the haveli, but

visitors are welcome to enter and see the haveli for themselves. (Interestingly,

the family name Saraf is a generic name for a banker or moneylender. It

has its roots in the Arabic sarraf, which was borrowed into Persian as

saraf, and became anglicised during the days of the British Raj as Shroff).

5)

Inside Mandawa, a town singularly rich in gorgeous havelis. And inside

one of the few havelis that actually charges an entry fee-- but with good

reason. The Jhunjhunwala haveli in Mandawa finds its way into coffee table

books on the strength of this intricately painted ceiling and the walls

below it. The ubiquitous Krishna again appears here with his beloved gopis--

milkmaids-- in an extravaganza of colours highlighted with gold wash. 5)

Inside Mandawa, a town singularly rich in gorgeous havelis. And inside

one of the few havelis that actually charges an entry fee-- but with good

reason. The Jhunjhunwala haveli in Mandawa finds its way into coffee table

books on the strength of this intricately painted ceiling and the walls

below it. The ubiquitous Krishna again appears here with his beloved gopis--

milkmaids-- in an extravaganza of colours highlighted with gold wash.

As in other parts of Rajasthan, in Shekhavati too frescoes were originally

made by painting vegetable dyes onto wet lime plaster. The colour was allowed

to set along with the plaster, after which a second layer of plaster was

laid on top-- and the painting made all over again on the wet plaster.

The many layers, each with its own colours dried deep into the lime, made

the frescoes resistant to harsh sunlight.

Later havelis in Shekhavati used not just

vegetable dyes, but also imported synthetic colours. The vivid blues seen

in many frescoes, for instance, were brought all the way from Germany:

another testimony to the wealth of the local businessmen.

6)

Another view of the painted room at the Jhunjhunwala haveli in Mandawa.

The upper sections of the walls are, according to the young woman who opened

the room for us, studded with pieces of coloured glass that was imported

from Europe. The painting, at any rate, appears far superior to the slightly

tacky glasswork. The panels on either side of the central window depict

Marwari noblemen; the central panel below depicts the elephant-headed Hindu

deity, Ganesh. 6)

Another view of the painted room at the Jhunjhunwala haveli in Mandawa.

The upper sections of the walls are, according to the young woman who opened

the room for us, studded with pieces of coloured glass that was imported

from Europe. The painting, at any rate, appears far superior to the slightly

tacky glasswork. The panels on either side of the central window depict

Marwari noblemen; the central panel below depicts the elephant-headed Hindu

deity, Ganesh.

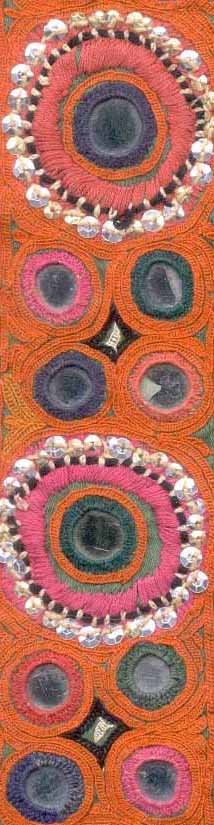

7)

Although not as popular as its better-known neighbour the Jhunjhunwala

haveli, the Gulab Rai Ladia haveli in Mandawa can boast of better glasswork.

The dwar-- the front door-- of the haveli is decorated with mirror and

glass, arranged in floral patterns along the façade. Above are tall

windows shuttered against the harsh summer sun, and-- on the top left of

the photograph-- a fading depiction of an elephant. 7)

Although not as popular as its better-known neighbour the Jhunjhunwala

haveli, the Gulab Rai Ladia haveli in Mandawa can boast of better glasswork.

The dwar-- the front door-- of the haveli is decorated with mirror and

glass, arranged in floral patterns along the façade. Above are tall

windows shuttered against the harsh summer sun, and-- on the top left of

the photograph-- a fading depiction of an elephant.

8)

One of the best-maintained havelis in all of Shekhavati, the Chokhani haveli

in Mandawa is a huge mansion divided into two parts. One part is occupied;

the other lies vacant but is open to visitors. Inside, the walls, arches,

balconies, and jharokhas (windows) of the haveli are covered with intricate

and beautiful frescoes; outside, time has taken its toll on the paintings,

and parts of them are disintegrating. 8)

One of the best-maintained havelis in all of Shekhavati, the Chokhani haveli

in Mandawa is a huge mansion divided into two parts. One part is occupied;

the other lies vacant but is open to visitors. Inside, the walls, arches,

balconies, and jharokhas (windows) of the haveli are covered with intricate

and beautiful frescoes; outside, time has taken its toll on the paintings,

and parts of them are disintegrating.

In this photograph, a camel cart stands in the shade of a neem (margosa)

tree outside the Chokhani haveli. The camel looks on at the caparisoned

elephants painted on the boundary wall, while the man takes a breather.

Mandawa is full of similar scenes, simply because it’s so full of havelis.

In nearly all of Shekhavati’s towns, you’ll find a haveli down every street;

in Mandawa, you’re likely to find a dozen or so down every street. Ornate

plaster scrollwork and fading frescoes adorn every second building here--

even the building that houses the State Bank of Bikaner and Jaipur has

a charming façade painted over with European soldiers on the march.

9)

The town of Fatehpur has its share of havelis, but few are as beautiful

or well maintained as those in nearby towns like Mandawa. The newly restored

Nadine Le Prince Haveli and Cultural Centre (locally known as the 'Angrez

ki haveli’-- the haveli of the English) is an exception. Painstakingly

(and expensively) restored at a cost of close to Rs 10 million, the haveli

is richly painted inside and out. The photograph shows a section of the

outside wall, adjacent to the street, painted mainly in shades of red and

blue, and depicting scenes from court life. 9)

The town of Fatehpur has its share of havelis, but few are as beautiful

or well maintained as those in nearby towns like Mandawa. The newly restored

Nadine Le Prince Haveli and Cultural Centre (locally known as the 'Angrez

ki haveli’-- the haveli of the English) is an exception. Painstakingly

(and expensively) restored at a cost of close to Rs 10 million, the haveli

is richly painted inside and out. The photograph shows a section of the

outside wall, adjacent to the street, painted mainly in shades of red and

blue, and depicting scenes from court life.

The scenes are very Indian, which sets the haveli apart, since it was considered

fashionable to include scenes relating to Europe, or at least to modern

times, in paintings. Some literally went out of their way to ensure that

the frescoes were up to date: Anandilal Poddar, who constructed the Dr.

Ramnath A Poddar haveli in Nawalgarh in 1902, sent the artist all the way

to Bombay so that he could see what a train looked like-- and then reproduce

it on the wall of the haveli.

10)

A carefully executed example of how Shekhavati frescoes happily blend India

and Europe: this painted archway is neatly divided into two panels. The

one on the left depicts scenes from the life of the Hindu god Krishna,

while the one on the right depicts European nobility-- perhaps even royalty.

Combining Hindu mythology with European elements may seem odd, but at least

in this particular example, they’re not part of the same picture. 10)

A carefully executed example of how Shekhavati frescoes happily blend India

and Europe: this painted archway is neatly divided into two panels. The

one on the left depicts scenes from the life of the Hindu god Krishna,

while the one on the right depicts European nobility-- perhaps even royalty.

Combining Hindu mythology with European elements may seem odd, but at least

in this particular example, they’re not part of the same picture.

Other artists of the

era apparently had few qualms about merrily mixing the elements of their

art: the Piramal haveli in Baggar, for instance, has a painting that shows

a Hindu deity flying an aeroplane.

(--December 2005)

|