Senior wives playing chaupar (Lucknow, c.1790)

Source: A Second Paradise: Indian Courtly Life 1590-1947, by Naveen Patnaik (New York: Metropolitan Museum, 1985), p. 72; scan by FWP, Sept. 2001.

"Senior Wives Playing Chaupar in the Court Zenana with Eunuchs; possibly by Navasi Lal after a lost original by Tilly Kettle. Mughal, Lucknow; ca. 1790; 18 x 10.5 cm. James Ivory Collection."

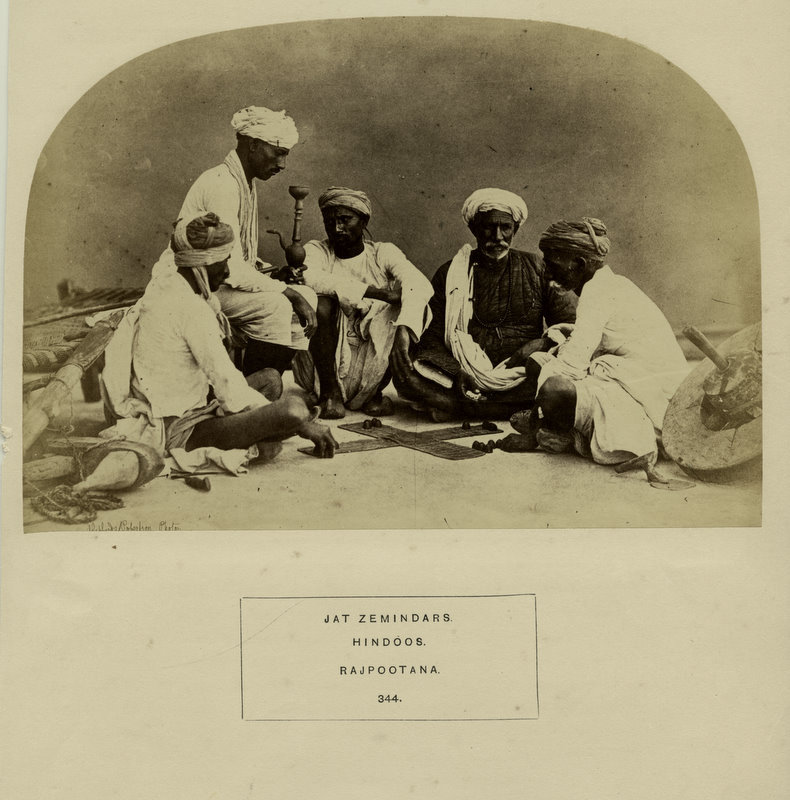

"Group of Marwaree men playing chess [actually pachisi]," a photo perhaps by Taurines, c.1880's

Source: ebay, Nov. 2007

P A C H I S I [also called chausar or chaupar] is the national game of India. It is played in palaces, zenanas, and the public caffés.M. L. Rousselet, speaking of the Court of the Zenana in the palace at Futteypore, says [in India and its Native Princes, 1876]— "The game of Pachisi was played by Akbar in a truly regal manner. [258] The Court itself, divided into red and white squares, being the board, and an enormous stone raised on four feet, representing the central point. It was here that Akbar and his courtiers played this game; sixteen young slaves from the harem wearing the players' colours, represented the pieces, and moved to the squares according to the throw of the dice. It is said that the Emperor took such a fancy to playing the game on this grand scale that he had a court for pachisi constructed in all his palaces, and traces of such are still visible at Agra and Allahabad."

Mr. Bellasis says [in the Calcutta Review, 1867]— "There is a gigantic pachishee board at the palace at Agra, where the squares are inlaid with marble on a terrace, and where the Emperors of Delhi used to play the game with live figures,— a similar board existed within one of the courts of the palace at Delhi, but it was destroyed in the alterations after the Mutiny."

In one of the early numbers of the Calcutta Review [xv, 1851] we read— and this boisterous excitement in playing the author has seen in his own experience— "The [259] combatants breathe hatred and veangeance against each other: the throws of the dice are accompanied with tremendous noise, and the sounds of "kache-baro" and "karo-pauch" and "baro-pauch" are heard from a considerable distance. It is altogether a lively scene, in strong contrast with the apathy generally attributed to the Bengalis.... In the cool of the evening parties of respectable native may be not unfrequently seen sitting under the umbreageous Bakul, and amusing themselves with chess, pasha, or cards. Laying aside for a season the pride of wealth and even the rigorous distinctions of caste, Brahmins and Sudras may be seen mingling together for recreation. The noisy vociferations and the loud laugh betoken a scene of merriment and joy. The huqah, a necessary furniture of a Bengali meeting place, is ever and anon by its fragrant vollies ministering to the refreshment of the assembly: while the plaudits of the successful player rise higher than the curling smoke issuing from the cocoanut vessel."

The board is generally made of cloth cut into the shape of a cross, and then divided into squares with embroidery; one such in my possession... is of red cloth embroidered with yellow silk: another... is from Delhi, and is made of glass beads beautifully worked, and having both sides alike, and even the men and dice are worked with beads in like manner. Each limb has three rows of eight squares. The outer rows have roses or ornaments at certain distances, which serve as castles, in which pieces are free from capture. The extreme square of [260] the central row is also a castle. The castles are open to both partners. Pieces may double on other spaces, but it is at their own peril.

These castles are placed on the board so that from the centre or home, where all the pieces start from, going down the middle row, returning on the outside, and then on to the end of the next limb, will be exactly 25, hence the name of the game; and from the castle in the middle of the nearer side of one limb to the middle of the further side of the next limb will be 25; from the middle of the further side of one limb to the middle of the nearer side of the opposite limb will be 25 + 1 (grace), which grace may be played separately; and from the extreme end of the fourth limb to the home of the first limb will also be 25, and out.... Any number of pieces of a player or of his partner are safe in these castles, and an enemy cannot enter: but if pieces double in any other squares, they can be taken off by a single piece at one stroke on throwing that number.

The game is played by four players, each having four pieces. The two opposite sides are partners, and they win or lose together. In order to distinguish them better, the yellow and green should play against the red and black. Each enters from the centre, then goes down the middle of his own limb, and then round the board, returning up the centre of his own limb from whence he started. On going up the central line of one's own home, the pieces are turned over on their side, to show that they have made the circuit. They can only get out by throwing the exact number. The pieces move by throws of six cowries; these throws count as follows [261]:

6 with mouths down and 0 up = 25 and grace, and play again 5 with mouths down and 1 up = 10 and grace, and play again 4 with mouths down and 2 up = 2 3 with mouths down and 3 up = 3 2 with mouths down and 4 up = 4 1 with mouth down and 5 up = 5 0 with mouth down and 6 up = 6 and play again Here there is a diversity in different parts of India. In some parts seven cowries are used instead of six, and the throws are different: sometimes they are 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 12, and 25; sometimes 2, 3, 4, 6, 10, 12, 25; and sometimes 2, 3, 4, 7, 10, 14, 25, and 30.

The cowries and dice are thrown by the hand, but the latter generally roll down an inclined plane, the natives shouting as they roll for good luck.

When graces are thrown the grace may be played separately. On taking a piece the player may throw again; and consequently, if a piece is taken by a 25, a 10, or a 6, the player will have two more throws, one for the throw, and one for taking a piece.

In commencing the game the first piece may be entered whatever throw is made, but the other pieces can enter only with a grace. So, likewise, a piece taken up can enter only with a grace. The pieces move against the sun. A player may refuse to play when it comes to his turn, or he may throw and then refuse to take it. He may do thiseither because he is afraid of being taken, or to help his partner.

On reaching the extremity of the fourth limb he may wait there till he gets a "twenty-five" and thus gets out at one throw. Should his partner be behind in the game, he must keep his own pieces back in order to assist him, and so by blocking up the way, prevent the adversaries from following close behind him, and [262] thus hinder their moving, or taking them if they do move. Tyros in the game, forgetting this principle that both parties must win or lose together, or intent solely upon their own desire of being first, make haste to get their own pieces out, thus leaving their partners in a lurch; who, if much in the rear, are sure to lose the game, as their opponents have two throws to their one, and are enabled to keep close behind them, and thus trip them up.

Sometimes the forward player, on arriving at his own limb, instead of turning his piece over and going up the centre, may, if permitted, run all round the board a second time, in order to assist his partner. Sometimes the player who is out first is permitted to give his throws to his partner, but this is not the game.

The ladies of the harem who play this game are said [in the Calcutta Review] to call it Das-Pauchish, taking this name from the two principal throws, ten and twenty-five.

Two games, being modifications of the Pachisi, are so distinct as to acquire specific names, Chausar and Chauput. These are slight varieties of Pachisi in move and play, in different parts of India.

== Glossary index == map index == Indian Routes == fwp's main page ==