|

|

Stranded Pakistanis Long for a Country That Left

|

|

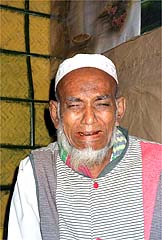

By BARRY BEARAKPakistanis stranded in Bangladesh live in 66 camps like this one, top, in Dhaka. Muhammad Jainul Abedin, 70, above, who has lived in Rangpur camp for 29 years, wept and said, "I am going to die here," and wept. The Pakistanis were left behind in 1971 when East Pakistan became the independent Bangladesh.

RANGPUR, Bangladesh -- The world ceaselessly churns out human tragedy. The newly conquered. Newly dispossessed. Newly hungry. Newly diseased. Newly destitute.

One calamity overtakes another, and the 240,000 "stranded Pakistanis of Bangladesh" know they are the leftover unfortunates of distant yesterdays.

For 29 years, they have been spread across this nation in 66 squalid camps, each a tightly packed thatch firetrap. They live as refugees, though theirs is a more peculiar predicament. They did not leave their country; their country left them.

In 1947, the newly created Islamic Republic of Pakistan had an East and a West, two large chunks of territory with the behemoth India in between. In 1971, the East won a war of independence and became Bangladesh.

Left behind were those who had been loyal to Pakistan, some of them active collaborators. In victory, they would have been patriots. In defeat, they were traitors.

They sold their property -- or had it confiscated. They were herded into camps, often for their own protection. Their decided preference was to leave the new nation and go to the part of Pakistan that still existed. They expected to be welcomed. Their waiting began. Three decades later, they wait still.

But for what? Once, they thought of Pakistan as the promised land. Now, many are unsure they would go even if they had the chance. Steeped in inertia, enmeshed in poverty, they are waiting because waiting is what they do. Even the most stalwart now wonder whether they have sacrificed their lives to a sad folly.

"Look at me -- I am going to die here," said Muhammad Jainul Abedin, a frail 70-year-old. He lives in a camp in Rangpur, a small city in the northwest. A stroke has disabled his arm. His spirit suffers a paralysis as well.

His face crumpled with tears. "Who thought we would spend 30 years living in a filthy camp?" he said.

Mr. Abedin's son, Muhammad Zabed, was standing near. Like most families, they live in a cramped shack, their small space reconfigured into tinier nooks with the marriage of every son and the birth of each baby. Surreally, on one wall they have hung posters of elegant American farmhouses, with broad porches behind white picket fences.

"They make the room look beautiful," Mr. Zabed said. "Of course, once you walk outside, you are back in the filth."

The government provides the camps free electricity, water and a ration of wheat. The camps are not prisons. People can move out, though few do. Without money, they say, there is no way to make a fresh start. They have grown used to their limbo, waiting futilely as Bangladesh and Pakistan figure out which is to keep them.

"These two countries, they each try to throw the ball -- or should I say the people -- into the other's court," said Muhammad Mohi-Us Sunnah, the legal officer for the office of the United Nations high commissioner for refugees in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. "It's quite pitiful, really. And no one seems to be doing anything about it."

Indeed, his own agency offers no help. The stranded Pakistanis do not qualify under the United Nations definition of refugees. They are waiting to flee, but have not yet fled.

"There is no one but Allah on our side," said Abdul Jabbar Khan, one of the stranded, though others in the room suggested that even God had tired of their cause.

Here in Bangladesh, as well as in Pakistan, people in the camps are known as Biharis. In 1949, when India and Pakistan were loosed from the British Empire, millions of Muslims left largely Hindu India, some going east, some west.

Those going east were called Biharis because most had come from the Indian state of Bihar. In India, their religion had made them a minority. In East Pakistan, their language did the same. The majority spoke Bengali. They spoke Urdu.

The Biharis never quite melded into the larger population. After Bangladesh became independent, their preference for Pakistan seemed natural, and in those early days, 160,000 made the journey. But then the flow suddenly stopped, with each nation blaming the other for the halt.

Ever since, the "repatriation" has suffered fits and starts -- but mostly fits.

In 1979, 50,000 of the Biharis tried to walk their way to Pakistan. They were turned back at the Indian border. In 1988, the Muslim World League, a charity, formed a trust fund with the government of Pakistan to provide an airlift for these "hostages of patriotism." They raised a substantial sum, but it lies unspent in a bank.

Political instability in Pakistan has been a major hindrance. Elected officials and military rulers change places with immoderate frequency. Ethnic distemper pervades Karachi, the presumed spot where many of the Biharis would relocate. And Pakistanis who migrated from India are considered troublemakers by much of the establishment.

Until a military coup last October, Muhammad Arshad Chadri held the feckless position of counselor general for the return of stranded Pakistanis.

He is a disappointed man. "Anyone with compassion who has visited the camps would understand this is a human rights issue," he said. "But where are the human rights groups? Where are the nongovernmental organizations?"

The longtime leader of the stranded Pakistanis is Nasim Khan. He is 77, a white-haired man with a heart condition and cataracts. For three decades, he has fed his followers on a chimera. They have flown the Pakistani flag and celebrated the Pakistani holidays. He made them homesick for a place they had never been.

Most people in Bangladesh -- even in the camps, the government, the news media -- think Mr. Khan still clings to a dream of deliverance. But his ideas seem to have taken a somersault. In a recent interview, he said, "Pakistan is not the land of honey and milks."

Indeed, he now concludes that the stranded Pakistanis would be better off as naturalized Bangladeshis, especially if they can negotiate a "package deal" with reparations for lost property.

The thinking of the leaders seems to be catching up to that of the followers. In an informal survey, C. R. Abrar, who heads a research project on migratory movements at Dhaka University, found that 60 to 70 percent of those in the camps would now prefer a permanent home in Bangladesh.

"I was brought to a camp as a baby, and now I have my own sons," said Abdur Rouf, 30, a sandal maker. "My future is gone, but what about theirs? Our lives have been one big misunderstanding."

In a small meeting room in Rangpur, Mr. Khan, the venerable and eloquent voice of the stranded, sat before a picture of himself and spoke of his life and cause.

The room was crowded. People were asked: would you prefer to live in Pakistan or Bangladesh? With their leader looking on, the stranded performed dutifully. Hands lifted high, they voted for a life in Pakistan.

Mr. Khan leaned to his side and lowered his voice to a whisper. For 29 years, he had been a champion to a quarter of a million people, the symbol of their expectations.

And yet now he softly said, "Why do we need to go to Pakistan?"