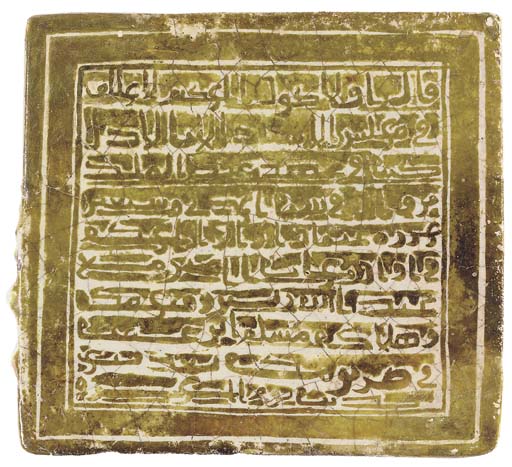

A remarkably interesting early calligraphic tile, probably 8th century

Source: http://www.christies.com/LotFinder/search/LOTDETAIL.ASP?sid=&intObjectID=4272498&SE=CMWCAT03+675760+%2D724344296+&QR=M+1+0+Aqc0000900+643310++Aqc0000900+&entry=india&SU=1&RQ=True&AN=1

(downloaded Apr. 2004)

"AN UMAYYAD OR EARLY ABBASID LUSTRE POTTERY TILE, PROBABLY BAGHDAD, DATED AH 71/690-1 AD, BUT PROBABLY 8TH CENTURY. A square tile with ten lines of cursive early script within clouds, plain striped border, one corner restored, otherwise intact. 5¾ X 6¼in. (14.6 x 16cm.)

Lot Notes: A suggested reading of the inscription:

"First the wise said to the confederates at the assembly of the master written during the time of 'Abd al-Malik Marwan (sic.) in the year seventy one (691-2 AD). It was written by 'Uthman. In times of governing with 'Abdullah Zubayr (sic.) and and the death of Muslim ibn 'Uqba on the road to Mecca after [of M]edina ."The fact that it is written as 'Abd al-Malik Marwan and not 'Abd al-Malik ibn Marman; and similarly 'Abdullah Zubayr instead of 'Abdullah ibn Zubayr is confusing. The only way to understand the above is the Persian way where by adding an izafeh 'Abd al-Malik-i Marwan, it would make it the son of.

This is certainly the earliest date on any piece of Islamic pottery. The death of Muslim ibn 'Uqba is noted as being in 683 AD, shortly before the stated date of the event recorded on the tile. The caliph 'Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan reigned between 65/685 and 86/705, so the date on the tile is fully consistent with his reign.

The introduction of lustre pottery is thought to have come as a development of lustre painting on glass which was developed in Egypt in the 8th century. Its use on pottery is thought to have begun in the 9th century (Porter, Venetia: Islamic Tiles, London, 1995, pp.21-31). Only two sites are known for certain to have been decorated in lustre tiles; it is these two that have produced the only Abbasid tiles known. One of these is the palace of Jawsaq al-Khaqani at Samarra whose tiles are very strongly influenced by Byzantine motifs and do not relate at all in design to the present piece. The other is the Great mosque at Qairouan, whose tiles are recorded as having been partly imported directly from Baghdad and partly the work of a potter who came from Baghdad. The Qairouan tiles are well published by Georges Marçais (Les Faiences à reflets métalliques de la Grande Mosquée de Kairouan, Paris, 1928) amongst other works.

Both sets of tiles indicate that the earliest lustre painting that was developed was in polychromy. Monochrome lustre tiles of this period are not documented, although the vast majority of 'Abbasid lustre vessels are monochrome. Yet the glass designs from whose technique they were inspired were monochrome lustre. Logic would make one think there would have been a period of monochrome lustre experimentation before the full polychrome glory appeared. But no trace of it is thought to remain.

This tile shares some features with those in Qairouan. The tone of lustre is one that is found there. The Qairouan tiles tend to have a thick plain outer lustre border, while sometimes they have, as here, a double plain stripe border (Marçais, op.cit, pl.IV, nos.20 and 22 for example). Some of them also have calligraphy arranged in lines of kufic. In one tile there is even the impression that, having drawn a panel of kufic or imitation kufic, the painter then filled in the interstices as happens on our tile (Marçais, op.cit., pl.XII, no.68). It has transformed the panel into a decorative overall design, but there is still the feeling that there was some sort of inscription under it.

In contrast to our tile however the kufic in all cases is constructed along a pre-drawn base-line, and appears to be more repeated letters rather than an attempt to write meaningful phrases. The closest similarities to the calligraphy on our tile are to be found in informal documents dating from the early Islamic period. However they are almost all done with an assured hand, whatever the style, while this tile has all the clumsiness of somebody trying to write neatly with a brush that he is not accustomed to write with, or else in a medium that is presenting him with problems. Thicknesses of strokes vary considerably, and letters are not consistently formed. There is also no hint of the slant in the script that writing with a pen, even at this time, frequently displays. It is thus almost as if the background blocks of lustre have been painted in after the script in order better to give the impression of this being written in straight lines! At times he adapts his style almost into a box-like construction, as in much of the third line, while in others it becomes very rounded and lacking in control as, particularly, in the ninth line. In these circumstances it is difficult to draw conclusions from the script. Comparing it with early scripts, such as those discussed by Geoffrey Khan (Arabic Papyri - Selected Material from the Khalili Collection, London and Oxford, 1992, esp. pp.27-39 "problems of dating") does not lead to any consistent conclusion. The closest similarities however seem to be with a papyrus dated to the 2nd/8th century (Khan, Geoffrey: Bills, Letters and Deeds, London, 1993, no.34, pp.,80-1).

What we can be sure of is that this script is not the same as that which appears on numerous pieces of Abbasid pottery. That has more consistency, particularly in terms of the thickness of line, tends to have marked upper terminals of the hastae, and, like the Qairouan tiles, has a very strong base line. With an inscription of this length it is very unlikely that the person who commissioned the tile would have opted for this script if there was a well-established tradition of calligraphy in lustre. Again therefore this strongly indicates a date earlier than the general corpus of Abbasid pottery.

We cannot be sure therefore precisely when this tile was actually made. It seems ambitious to suggest that lustre pottery existed in this tile over a century before any other known instance, especially since there is every reason to think that the inscription refers to an event in the past, and that therefore we are not fixed to the year AH 71. But a date before the Qairouan tiles, meaning our tile being created at a time when the technique was still in its infancy, seems most probable. The size of the tile, the experimental nature of the decoration, and yet the considerable historical importance of what is actually recorded in the inscription all converge towards a date well before the mid 9th century, when the major renovation program at Qairouan was at its height.

This is a remarkable survival, a unique document from the early Islamic period,

a tile which contains more historical information than all the other pottery

of the Ummayyad and Abbasid periods put together."