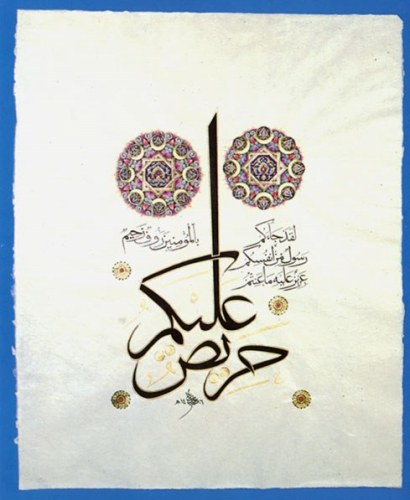

"Anxious is He over you," a piece by the American calligrapher Muhammad Zakariya

Source: http://www.islamicart.com/main/calligraphy/catalog/usa.htm

(downloaded April 2000)

"U.S.A. 1985-1986. Calligraphic composition. Ink, gouache and gold on paper, 25 3/4 x 21 1/4 in. Malaysia, private collection. Geneva, Jean-Paul Croisier collection.

The inscription consists of Surah IX, aT-Tawbah, verse 128:

Now hath come unto you An Apostle from amongstIt is written in Muhaqqaq script, with the words "anxious is he over you" in large Thuluth outlined in gold. Muhaqqaq, which means "meticulously produced", was standardized by Ibn Muqlah and reached perfection at the hands of Ibn al-Bawwab and Yaqut al-Must'asimi. Like Naskh, Muhaqqaq became an extremely popular script for copying Qur'an. Its shallow sub-linear curves and horizontally extended mid-line curvatures, combined with its compact word-structure, give it a leftward-sweeping impetus. Its varieties range from a somewhat rugged script to writing with delicate outlines and soft curves, and a bolder type with characteristics of both Thuluth and Naskh.

Yourselves; it grieves him that you should perish; Ardently

anxious is he over you: to the believers is he the most kind

and merciful.

The calligrapher of this composition is Mohammed Zakariya, a well-known modern exponent of the classical style, usually working in a manner which shows his interest in the Ottoman masters of the last century. Compositions of this type originated with Mustafa Raqim (1757-1826) and became popular in 19th century Turkey. However, the vividly colored roundels are based on 14th-century Iranian manuscript illuminations. The composition thus has diverse artistic and calligraphic antecedents. This piece shows the calligrapher's skill as a designer."

Muhammad Zakariya

Source: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/islamic_medical/calligraphy/calligraphy.html

(downloaded May 2002)

"Salvation is in sincerity," calligraphy by Muhammad Zakariya

Source: http://www.mideasti.org/library/islam/titlepage.htm

(downloaded Dec. 1999)

Information about the calligrapher from this website:

"Mohamed Zakariya is an Islamic calligrapher, artist, and maker of custom instruments from the history of science. Born in Ventura, California, in 1942, he began his study of Islamic calligraphy with A.S. Ali Nour in Tangier and London in 1964. After continuing his studies independently at the British Museum, he was invited in 1984 by the Research Center for Islamic History, Art, and Culture (IRCICA) in Istanbul to study with two celebrated Turkish calligraphers: Hasan Celebi and Ali Alparslan. In 1988, Zakariya received the prized icazet (diploma) in sulus/nesih script from Mr. Celebi in a ceremony in Istanbul, and in 1997, he received the icazet in ta'lik from Dr. Alparslan.

Zakariya has presented numerous workshops and lectures on Islamic calligraphy,

and his calligraphic works have been exhibited widely. In this country,

for example, his work has been shown at the Smithsonian Institution's Renwick

Gallery and S. Dillon Ripley Center and at the Klutznick National Jewish

Museum in Washington, D.C.. He has also shown his calligraphy and given

demonstrations in conjunction with Islamic art exhibits at the Metropolitan

Museum of Art in New York and the Walters Gallery in Baltimore."

ABOUT MY WORK (Statement by the calligrapher)

"The temptation of Islamic reformers is to reject, in the name of modernity, anything they consider old-fashioned or out-moded. When it comes to classical calligraphic art and its associated disciplines, that argument might have some small merit, but the tendency is to throw the baby out with the bath water. The consequences of this attitude have been catastrophic to the original arts themselves, to the artists, to connoisseurs, and to critics. The reformers' argument seems to be that the classical art is moribund, lacking in originality, and irrelevant. In many cases that is, superficially at least, true. Yet all the great calligraphers were originators and innovators, as are the best of today's masters, such as Hasan Celebi. Indeed, late 20th-century Islamic calligraphy is alive and well -- and, although the developmental and evolutionary chain is still intact, the art today is quite unlike its precursors in all but spirit.

In my own interpretation of Islamic calligraphy, I have tried to stay as close to the classical manner as possible, from the roots up. In the 37 years I have been developing my approach, I have worked through the art from its very origins, through its many technologies and its varied regional, epochal, and cultural strains. Finally, reaching a plateau in the 1980s, I took the sincere advice of colleagues and began to learn calligraphy all over again in the Ottoman manner, under the direction of Hasan Celebi and Ali Alparslan. It was an artistic revelation.

The Ottoman experience was both qualitatively unique and the last great experiment in Islamic civilization. Ottoman civilization was, like American society, international and multicultural. Although their empire was tragically flawed, Ottoman rulers -- especially those of the 19th century -- tackled the most difficult social and political problems with intelligence and sincerity. During their struggle to save their foundering state, the Ottomans supported the arts and allowed them to flourish to unprecedented degrees. Under the Ottomans, the calligraphic arts were accorded the status of fine arts, and many of their practitioners achieved places of honor. It was during this time that Islamic calligraphy rose to its greatest heights.

Therefore, while I find great value in exploring such aspects of the art as Hispanic/Maghribi script and illumination, I had to seek out the best place from which I, as a Muslim of American/European background, could jump off to the present and the future. For me, that was the Ottoman method, which is both more modern and more rigorous as to standards. In its modern Turkish guise, this method is still the most vital branch of the ancient tree.

For my calligraphy, I make my own tools and materials whenever possible, using the tried and true recipes and methods of the masters. Still, I believe some flexibility is needed to achieve certain effects. For example, although I produce all my own marbled papers according to the Turkish ebru method, I use different color schemes and patterns so that my work, while consistent with itself, is not derivatively Turkish. In the same vein, I do not follow the current trend in illumination now favored by Turkish artists. Instead, I base my illumination schemes on what is often called Turkish Baroque: Islamicized ornamental themes that are European in origin. This style of ornamentation, which found favor with the Ottomans, is intrinsically simpler and bolder than the immaculate, minuscule Persianate style now used in Turkey, and it leaves more room for experimentation.

For the modern Islamic artist, particularly the artist of Western birth, there is the persistent problem of ethnicism in contemporary culture. Are works of art written in Arabic, Turkish, or Farsi the exclusive preserve of those who, through birthright, can claim them as their own? If so, then my Western colleagues and I are interlopers, trespassers in someone else's vegetable patch, and our work is illegitimate. But if, as I believe, our work is legitimate, it is because we take the traditional Muslim position that such matters as ethnic exclusivity have no place in the religion and its arts, that the languages and arts of Islam are the heritage of all Muslims, no matter what their origins.

The great challenge for the modern Muslim artist is to present the great truths in a way that, while remaining loyal to the traditions of the past, is new and fresh and vital, marked by fine workmanship and sincerity and authenticity. In this way, the ancient texts can speak for themselves, revealing their meanings spontaneously to the viewer -- sometimes gently, sometimes grandly, from butterflies to thunderation.

Because the calligraphic arts are unbound by the need to represent objective reality, they are free from the cultural and political constraints associated with the pictorial arts. This sets the calligrapher free and, at the same time, adds new constraints. This constant tension between constraint, tradition, and standards makes Islamic calligraphy neither a representational art nor an abstract one but something entirely other, a living, evolving art of the word, of meaning itself." -- Mohamed Zakariya (http://www.mideasti.org/library/islam/zakaria.htm)

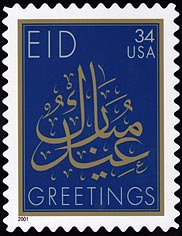

Mohamed Zakariya's US postage stamp, Sept. 1, 2001

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/2001/11/20/national/20STAM.html

(downloaded Nov. 2001)

New York Times, National, November 20, 2001

U.S. Muslims Push Stamp as Symbol of Acceptance

By LAURIE GOODSTEIN

For five years, American Muslims tried to persuade the Postal Service to issue a stamp commemorating a Muslim holiday. After all, they reasoned, there were stamps for Christmas and Hanukkah and even for Kwanzaa and Cinco de Mayo. To press the case, Muslim children wrote more than 5,000 letters to the postmaster general, and Muslim groups lobbied Congress.

They finally got their wish. The first American stamp with an Islamic theme was issued on Sept. 1, 10 days before Islamic terrorists crashed airliners into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon....

The new stamp, featuring gold Arabic calligraphy on a lapis background, commemorates the two most important Muslim holidays: Eid al-Fitr, the end of Ramadan fasting, and Eid al-Adha, at the end of the pilgrimage to Mecca.

"Our campaign is to make the Eid postage stamp permanent," said Aly Abuzaakouk, executive director of the American Muslim Council, which helped lead the drive to create the stamp. "For Muslims it is as if their country has recognized them."

The stamp was designed by Mohamed Zakariya of Arlington, Va., a noted Islamic calligrapher....

The stamp's designer, Mr. Zakariya, said: "I have an Arab friend who

is going to use it for Christmas cards and Jewish friends who are going

to use it for their holidays. People want to make a statement."