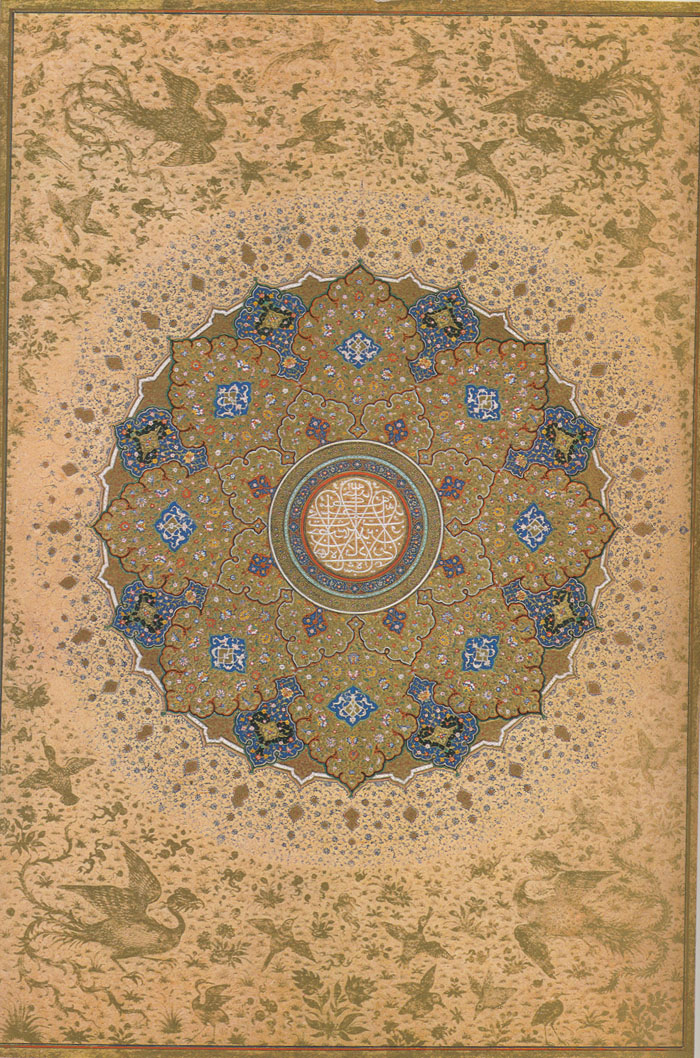

Shah Jahan's "shamsa" or rosette design.

Source: http://www.metmuseum.org/collections/view1.asp?dep=14&full=0&item=55%2E121%2E10%2E39

(downloaded May 2000)

*CLICK HERE for the Met's own image, with ZOOM capabilities*

"Rosette (Shamsa) bearing the name and titles of the Emperor Shah Jahan (r. 1628-58). Illuminated page or Shamsa (recto) / calligraphy (verso), 17th century; Mughal. Ink, colors, and gold on paper; 15 3/16 x 10 7/16 in. (38.6 x 26.5 cm). Purchase, Rogers Fund and The Kevorkian Foundation Gift, 1955 (55.121.10.39). From the Metropolitan Museum collection.

A "shamsa" (literally, "sun") traditionally opened imperial Mughal albums. Worked in bright colors and several tones of gold, the meticulously designed and painted arabesques are enriched by fantastic flowers, birds, and animals. The inscription in the center in the "tughra" ("handsign") style reads: "His Majesty Shihabuddin Muhammad Shahjahan, the king, warrior of the faith, may God perpetuate his kingdom and sovereignty." (W. M. Thackston, trans.)"

A much larger version of the shamsah

Source: Stuart Cary Welch, Imperial Mughal Painting. New York: George Braziller, 1978. Image: Plate 30, p. 99. FWP scan, Aug. 2001.

Commentary by Stuart Cary Welch, p. 98:

"This was the opening page to an album of calligraphies and miniatures assembled for Shah Jahan....But unlike Jahangir, whose ideas on painting differed from those of his father, Shah Jahan encouraged artists to continue painting as they had for his father. His pictures, therefore, are sometimes difficult to differentiate from Jahangir's, although their colors tend to be more jewel-like, and their mood is usually more restrained.

A serious collector of gems, many of which he ordered set into his renowned Peacock Throne, Shah Jahan insisted upon opulent perfection in everything he commissioned. The workmanship and sumptuous color of the rosette by a specially trained illuminator rather than figure painter, as well as its nobly designed calligraphic inscription, bring together qualities of architecture, jewelry, and painting. Indeed, this glorious design might be considered the embodiment of the verses inscribed in the emperor's Delhi Audience Hall, "If there is heaven on earth, it is here, it is here, it is here."

Such mathematically abstract and cerebral arabesque designs bring to mind the Mandalas of Buddhism and Hinduism, psychocosmograms designed for meditation. Here, the center of the composition can be interpreted as the pivot upon which all turns, the axis connecting the existential world with those above and below. It is no accident that Shah Jahan's titles are inscribed at the center of this heavenly image. As if to reinforce its celestial spirit, magnificent golden phoenixes, or simurghs, and other birds soar round the central figure."