FWP:

SETS == CATCH-22

SCRIPT EFFECTS: {33,7}

As so often in mushairah verses, from the first line we can't tell what's going on. Could the beloved be about to say something to the lover, something exceptionally cruel or kind? Could she even be about to kiss him? Could he himself be about to say something, and struggling to move his lips? Even when we are finally (under mushairah performance conditions) allowed to hear the second line, the punch-word that alone permits us to understand the verse is withheld until the last possible moment.

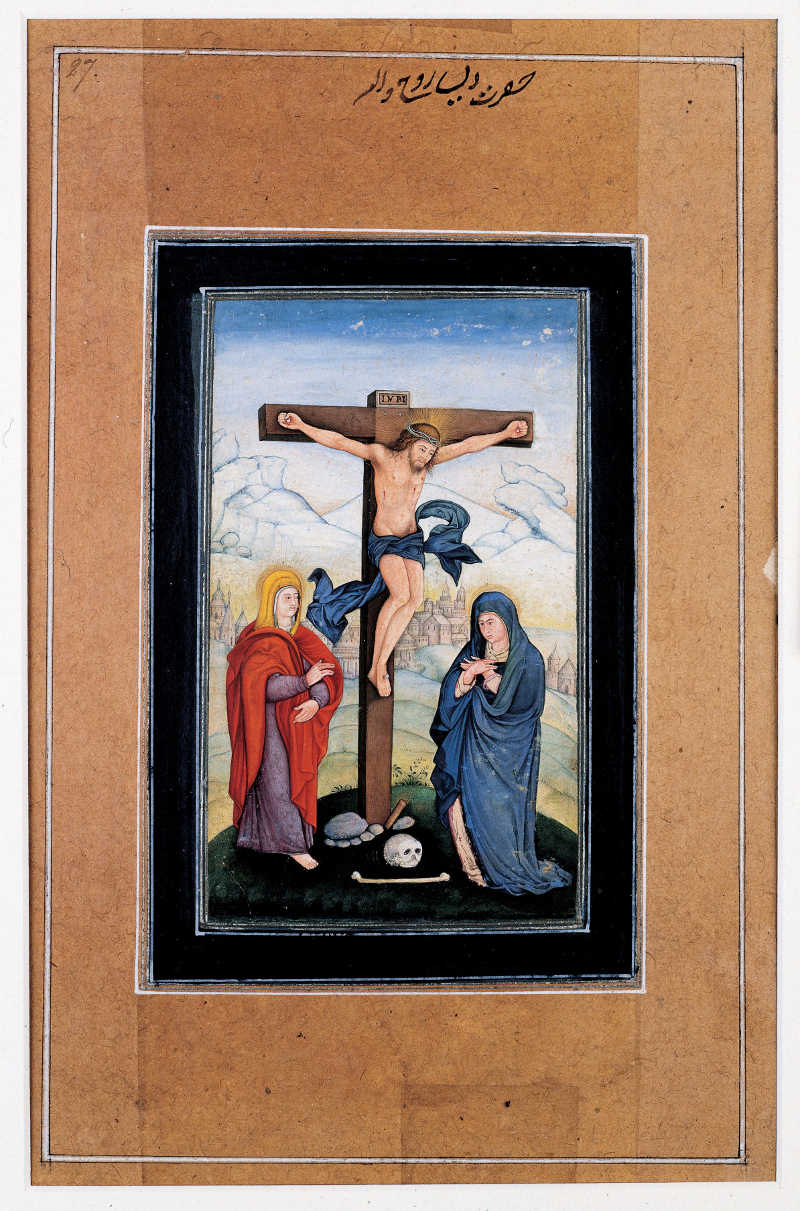

In Islamic tradition, the characteristic miracle of Jesus is to breathe on the dying or dead and thus restore them to life. The lover is so extravagantly weak, he has carried his passion so far, that he's more weak than Jesus's life-restorative power is strong. He's so weak that the tiny breeze of Jesus's breath blows out his flickering life, in a way that carries him beyond the possibility of revival. Thus the attempt at a cure is actually what kills him (as in {48,3}). The effect is an enjoyably paradoxical 'catch-22' one: the lover can't live unless Jesus breathes on him, but if Jesus breathes on him then he dies.

This verse is a member of the 'dead lover speaks' group; for others, see {57,1}. It's true that 'Ghalib' could be the subject in the first line, so that somebody else could be reporting Ghalib's death; but the remote placement of the 'Ghalib', and the strong tradition of self-address in the closing-verse, make this a secondary (and much less powerful) reading.

Note for fans of metrical technicalities: This verse has

been criticized for its 'audacity' with the rhyme-word.

The criticism is understandable: basically, it doesn't rhyme. In the word

is;aa , the chho;Tii ye at the

end is really only a bearer of a dagger alif . The name

is thus pronounced as though it ended with alif , not

ii . To use it as a rhyme-word in this ghazal is really

a remarkable liberty to take; but as Faruqi points out, it's based on earlier

Persian usage. As Nomanul Haq pointed out in a meter workshop at Penn (October

2005), everybody takes liberties in the opposite direction, using rhyme-words

of varying spellings if they have (more or less) the same sound. This verse

is an unusual example in which syllables of completely different sound

have been harmonized only by archaic Persian usage and (apparent, not real!)

spelling. For a similar case see {9,4}, in which taqv;aa has similarly been seemingly forced into being pronounced as taqvii .

Nazm:

In this verse, the subtle point of meaning is that the poet considers the movement of Jesus's lip to override the effect of the voice of Jesus. He says, I died from the shock of the very first movement, and was not equal to the breath of Jesus; that is, I had no encounter with the breath of Jesus, and because of my weakness I had no chance to hear the voice of Jesus. (10)

== Nazm page 10