FWP:

SETS == WORDPLAY

For more on har-chand , see {59,7}.

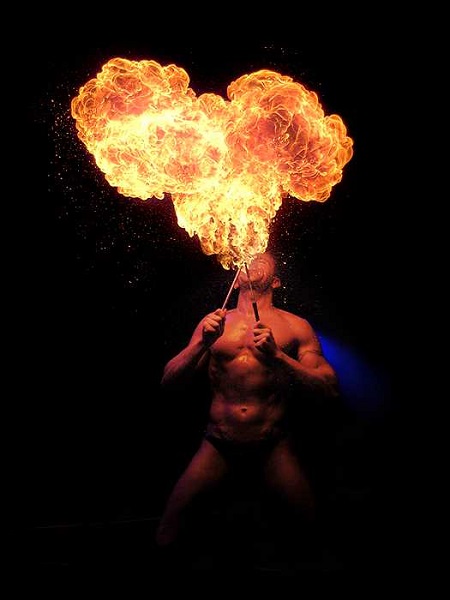

There are so many possible 'pre-poeticized' meanings of jalnaa (see the definition above)-- the verse simply throws in a couple of forms of the verb itself, and then adds an extra 'fire-shedding breath' for good measure. (On the subtleties of nafas , see {15,6}.)

In the first line, for example, the speaker somewhat petulantly asks why the self wouldn't 'burn' over its inadequate taste for oblivion. If it did burn, would it 'burn with envy' of those more successful lovers who manage to die quickly and completely, like Moths flying into a candle flame? Or would it 'burn with rage' at its own dilatory and lukewarm tendencies? Or would it 'burn with sorrow' or pity or some other emotion at the recognition of its own weakness? Or would it be so shamed by its remaining unburnt that it would just go ahead and 'burn up' and remove all cause for complaint?

Similarly, in the second line, 'we don't burn'-- but in what sense? Is the second line to be read as a sort of paraphrase of the first, with both describing the same situation? If so, 'burn' would surely be read the same way in both cases. But if the two lines are to be read separately-- and of course Ghalib gives us no hint about their possible relationship-- then the second 'burn' could be quite different from the first one. How about 'We don't catch fire, although the breath is constantly flinging out sparks.' Or: 'We're not jealous of the breath, even though it's so fiery and spark-shedding and we're not'. Or: 'Something's wrong with that inept breath-- it keeps uselessly shedding sparks, but nothing happens!'

No matter how the jalnaa meanings are

pieced together, I'm unable to find anything very interesting in them. This

verse feels like a casual spinoff from {76,2}

and {137,2}, which make much more compelling

use of the same kind of material.

Nazm:

That is, every breath enters the breast and gives rise to flame, and that very flame is the cause of life. Although in every flame the wellbeing of the body and the essence of the physical frame is diminished. From this it has emerged clearly that according to temperament and to the claims of its nature, every living creature has a relish for oblivion-- because the very flame that causes oblivion is life itself. But at the incompleteness of this relish for oblivion, the self 'burns', because it does not all at once burn it up. People who are acquainted with the author's biography will be astonished: from where did he learn this problem of the circulation of the blood [dauraan-e ;xuun]? (153)

== Nazm page 153