FWP:

SETS == IDIOMS; MUSHAIRAH;

REPETITION; WORDPLAY

EYES {3,1}

GAZE: {10,12}

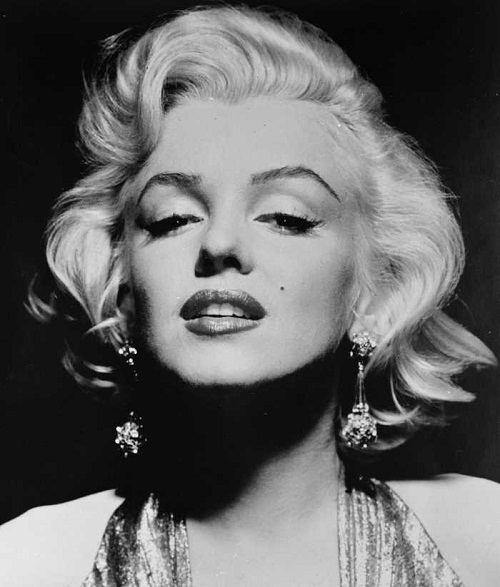

IDOL: {8,1}

Here we have a verse that makes excellent use of both wordplay and implication. The first line asks a piquant question-- why wouldn't the beloved make a practice of avoiding direct eye contact? (Although butaa;N is a Persian plural, it's often treated as though it referred to only one beloved.) Usually this is something the lover rails against and complains about-- why does he now seem to justify it, with even the extra emphasis given by an argumentatively, or even defiantly, repeated final phrase? The repetition amusingly and colloquially suggests both that he knows he's making an unpopular case, and that he's determined to make it. (Nazm is right to defend the verse from any charges of 'padding'; for more on this topic see {17,9}.)

Under mushairah performance conditions, we then have to wait a bit, before we hear the second line. And even then, as usual, the line withholds its punch-word until the last possible moment, so that the meaning hits us all at once, most delightfully. As Bekhud Mohani points out, the beloved traditionally has the 'eye of a sick person' [chashm-e biimaar] because her gaze is languid, lowered, averted.

Thus it won't surprise us if 'that sick person', her eye, lives soberly and abstemiously, and abstains from strong intoxicants, spicy foods, etc. The medical and quasi-moral (or sometimes even religious) associations of parhez are conspicuous and strongly marked; see the definition above. Thus the 'sick person' abstains from 'the gaze', as a prudent precaution or perhaps through a direct order from the physician.

Whose gaze? Naturally, this being Ghalib, we can't tell. Is it the hot, wild, demanding gaze of one or more lovers that might be a health hazard, or the intoxicating, conquering, and perhaps energy-draining gaze of the beloved herself? Either way, the beloved's lowered or averted eyes are a sensible medical precaution. Perhaps that's why her eyes are not just heedless, but 'absorbed in heedlessness' in what sounds like a very deliberate and systematic way.

The whole effect is thoroughly enjoyable. As so often, Ghalib has evoked an idiom, chashm-e biimaar , in both its colloquial sense (lowered eyes) and its dictionary meaning (a sick person's eyes). And yet-- he hasn't even used it. He has just left the pieces lying around for us to assemble.

For another verse that plays on chashm-e

biimaar without actually using the phrase, see {22,4}.

Nazm:

'That sick one'-- that is, the eye of idols. One point here worth reflecting on is that with the word ta;Gaaful the meaning was completed, but there was a need to add something to complete the line-- and in such situations the words that are added are usually padding, and are devoid of pleasure. For example, if someone were unpracticed [kam-mashq], he would here have inserted 'at every hour' [har gha;Rii], or 'night and day' [raat din], or 'when seated together' [ham-nishii;N], etc., and these words, like a padding of old rags, would seem bad. But with what excellence the author has completed the line! That is, he has brought in kyuu;N nah ho and repeated it, and thus he has increased the beauty. (224)

== Nazm page 224