Section 13 == *script chart*; *positional chart*; *more help*

The script part is from a manual of calligraphy, the rest a xerox-and-cut-and-paste job from Narang's reader.

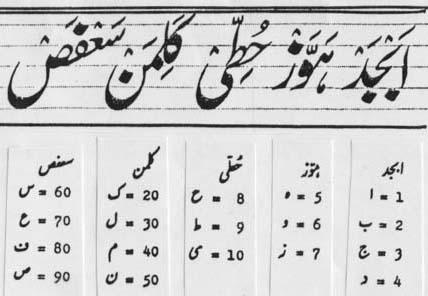

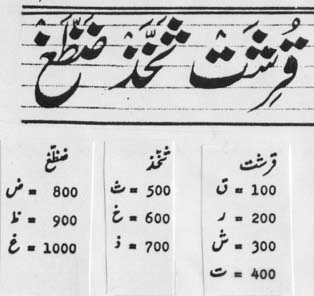

"Abjad" is the name given to the arrangement of the Arabic alphabet according to the occurrence of its 28 letters in a series of eight symbolic "words" (shown above), the first of which is "abjad" itself. (People used to memorize these "words," horribly clunky as they are, in order to have a quick key to the system.) Every letter has a numeric value in this arrangement, and can thus be used for composing tāriḳh , or chronograms. The order of the eight words and the numerical values of the letters are given above.

For printing convenience, here is a *single PDF page with the above numerical chart*.

The abjad system permits words and letters to encode dates. Dates are always understood to be those of the ḥijrī dating system, which uses lunar years starting from 622 A.D. when the Prophet left Mecca and took refuge in Medina. The system assigns to the twenty-eight letters of the Arabic alphabet the numerical values shown above.

Since the official list includes only the original letters of the Arabic script, the later-added Persian and Urdu letters are analogized: for example, gāf is treated like kāf . Here's the full set of equivalences:

pe is valued as be

ṭe is valued as te

che is valued as jīm

ḍāl is valued as dāl

;Re is valued as re

zhe is valued as ze

gāf is valued as kāf

baṛī ye is valued as chhoṭī ye

Arabic al

constructions go by script, not sound

a tashdīd creates a full

additional letter

The point of the system is to permit one to make chronograms, words or phrases such that the abjad value of their letters adds up to some important date to be remembered. Book titles were often made to encode the year of the book’s composition; expressions recording grief at the death of so-and-so were made to encode the year of the death; praise of a king’s military prowess were made to encode the year of some notable conquest. Chronograms are still made today among Urduu-knowers. To compose a chronograh is tāriḳh kahnā ; the whole art itself is known as fann-e tāriḳh . The word tāriḳh itself is also used to mean both "history" and "date."

13.2 = examples of tārīḳh composition

Some poets were exceptionally good at this art, and their skills were much in demand among their friends; Azad's *āb-e ḥayāt* (1880) and other such works are full of examples. Here are a few examples for practice.

Example one: Ghalib composed a chronogram for his own death: ġhālib murd , "Ghalib died." The phrase stands for the year 1277 A.H. (1860/1), which is worked out as follows, for a total of 1277:

| ġhain

= 1000 alif = 1 lām = 30 be = 2 |

mīm

= 40 re = 200 dāl = 4 |

(As it turned out, Ghalib didn't die in that year; he later joked about this fact in his letters. Azad's account of this: Pritchett and Faruqi, p. 510)

Example two: "786" is used by many Muslims as a numerical code for bā ism ul-lâh ul-raḥmân ul-raḥīm . Note: the "dagger alif " letters don't count.

| be = 2 sīn = 60 mīm = 40 alif = 1 lām = 30 lām = 30 he = 5 |

alif = 1 lām = 30 re = 200 baṛī ḥe = 8 mīm = 40 nūn = 50 |

alif = 1 lām = 30 re = 200 baṛī ḥe = 8 chhoṭī ye = 10 mīm = 40 |

| 168 | 329 | 289 |

(In case you find this example unusually difficult to work through, you're not alone. I never could have made it come out right without the help of my students.)

Example three: From Ralph Russell and Khurshidul Islam, Ghalib: Life and Letters (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1969), p. 247:

"Perhaps the best chronogram which Ghalib composed himself was that on the Mutiny-- rustkhez-i beja-- which he worked out and included in Dastambu.... The phrase is indeed an apt one, for it both fixes the date of the Mutiny and expresses Ghalib's view of it. It is not easy to translate. 'Unseasonable tumult' is an approximate equivalent, but 'unseasonable' does not convey the sense of outrage which 'beja' here carries. The other word, 'rustkhez', means 'Judgement Day', but is also used to describe any great tumult or upheaval, including emotional tumult.... If one adds up the numerical values of the letters of the word 'rustkhez' as written in the Urdu script, they give a total of 1277. From these must be deducted the combined values of the two letters 'ja'--for 'beja' may be read as a single word (and, indeed, must be so read to give the meaning required), or alternatively as two words 'be ja', meaning 'without (or, minus) ja'. The total of 'ja' is 4, and 1277 minus 4 comes to 1273, which gives the date of the Mutiny [of 1857] in the Muslim era."

In short, the analysis would look like this:

| re

= 200 sīn = 60 te = 400 ḳhe = 600 ye = 10 ze = 7 |

jīm

= 3 alif = 1 |

| 1277 | - 4 |

Many chronograms used to be made in ways that were tricky like this, or sometimes even more convoluted. Here's another tricky example from Ghalib: {202,9}. You'll find lots more examples in āb-e ḥayāt .

Example four: The chronogram title of Mir Amman's famous Fort William College version of "Story of the Four Dervishes" is bāġh-o-bahār ("Garden and Spring"); this title adds up to 1217 AH (1802/3), and thus encodes the year of composition. Try adding it up and see.

Example

five: It's

quite possible to do chronograms in Persian or Arabic,

even if you don't know the languages. According to

Bada'uni's muntaḳhab ul-tavārīḳh

(in Ranking's translation, vol. 1, p. 601), a poet

called Kahi composed a Persian chronogram that gave the

year of Humayun's death: 'Humayun Padshah fell from the

roof', or humāyūn pādshāh az bam

uftād . See if you can make it yield 962 A.H.

(1554/5). (With thanks to Joel Lee for providing this

one.)

Example six:

A chronogram composed by Nasikh on Jur'at's death, as

given in *Ab-e

hayat* is as follows: hāʾe

hindūstān kā shāʿir muʾā . It's pretty

straightforward, with the words yielding totals of 16 +

576 + 21 + 571 + 41, adding up to 1225, which

corresponds to 1810-11. Notice that the vāʾo in muʾā

must be treated as a chair for a hamzah

(as is the case with huʾā ).

Various small complexities like this must be allowed

for. But in practice, as a student one is usually

recapturing an already-known date, so it's possible to

work backwards from the desired figure and thus become

familiar with the subtleties of the system. (This

example is dedicated to my class of spring 2012.)

If you'd like to explore the

abjad system a bit more deeply, see also: Mehr Afshan Farooqi, "The Secret of

Letters: Chronograms in Urdu Literary Culture," in

Edebiyat 13,2 (2003), pp. 147-58: *this article* is available here

through the kind permission of the author.

And if you'd like to see some

examples of the system in action during its heyday,

here's a translation and analysis of *the inscriptions

on Amir Khusrau's tomb*, which are full of

chronograms.

And here is a "chronogram calculator" available through the websites of its two authors, *David Boyk* and *Daniel Majchrowicz*.