FWP:

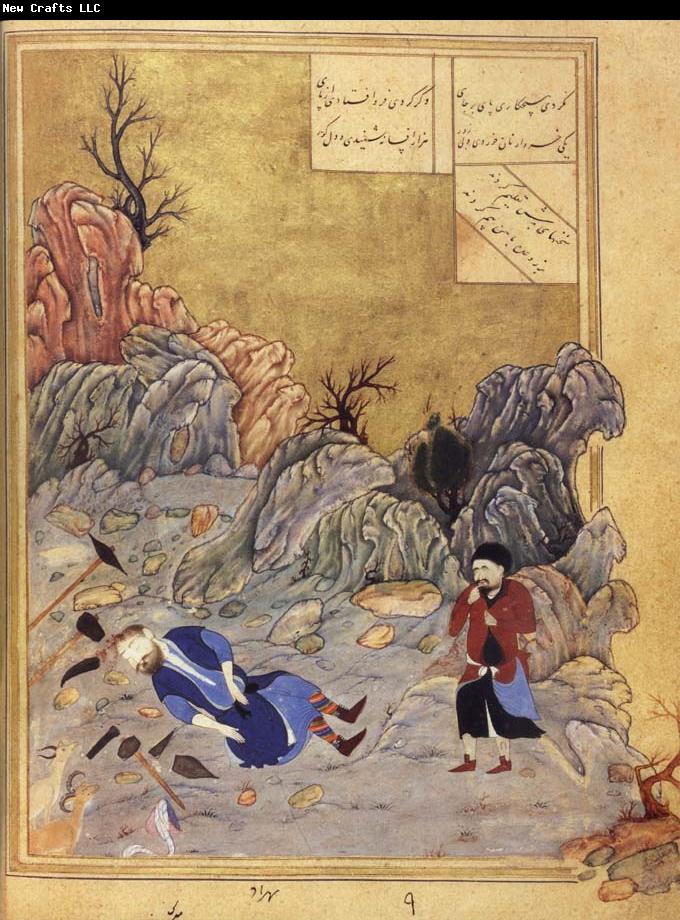

For the story of Farhad and Shirin, see {1,2}. Upon hearing (false) news of Shirin's death, Farhad smashed his head in with his own axe. Thus the literal meaning of sargashtah forms a nice resonance: he smashed his head in because his head was spinning. Usually intoxication is the lover's state; here, it is a miasma of conventions and externals that fogs the lover's brain so badly that he is reduced to using a conventional and external tool like an axe. Even more perfectly, the ;xumaar can be a sort of hangover (see the definition above), something left over after intoxication, something from which the lover would recover in time-- except that in this case there is no more time. For more on ;xumaar , see {12,2}.

For a more charitable interpretation of Farhad's prowess with an axe, see {36,8}. For further discussion of the general motif of snide remarks about earlier lovers, see {100,4}. And in {121,2}, Ghalib even offers a truly affectionate thought about Farhad.

Although everybody knows that officially ghazals are supposed to have an odd number of verses, we don't have to go any further into the divan than three ghazals before we discover that Ghalib doesn't set much store by that rule. More ghazals have an odd number of verses than have an even number, but the 'rule' is only a vague predisposition that the poets don't at all mind ignoring when they so choose.

Note for grammar fans: If you're curious about teshe

ba;Gair , see {59,1} for discussion.

Nazm:

It's a taunt against Kohkan for being so bound to custom and rule, which is contrary to madness and freedom.... If the intoxication of passion had been perfect, he would have died without smashing open his head. (3-4)

== Nazm page 3; Nazm page 4