FWP:

SETS == EK; IZAFAT; POETRY

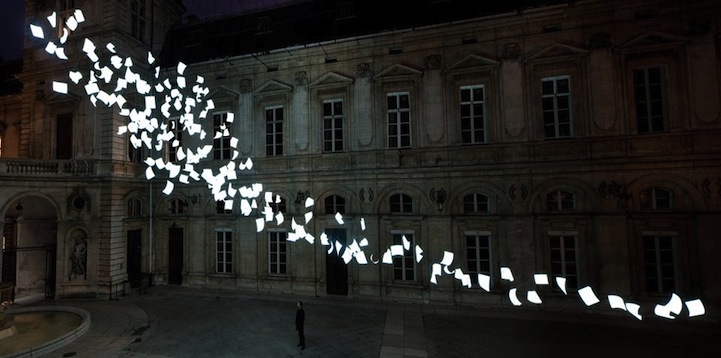

The 'lament of the heart' seems to be a frustrated poet-- gathering its pages only to disperse them, collecting them only to fling them to the wind. The word pareshaa;N , although it doesn't appear in the verse, hovers somewhere in the landscape; see for example {6,3}.

For a discussion of shiiraazah see {10,12}.

What does it mean to throw-- literally, 'give'-- the pages to the wind? On the face of it, to despair of one's creative powers, to reject one's own collected work. But in this case, the result was not chaos, loss, and blown-around bits of paper; the second line is very clear about that. The yaadgaar , 'memorial' or 'memoir', did not cease to exist. Far from it: it remained 'a single (or particular, or unique, or excellent) divan without a binding-thread'.

A paradox, even a miracle. How can a divan hold together in at least some fashion, so that it can be 'one' or a 'single' collection of poetry, if it doesn't have a binding-thread? Perhaps the wind will be its symbolic binding-thread-- perhaps to be unbound is its truest form of unity and self-expression. (Consider some of the meanings of {18,2}, earlier in this ghazal.) Perhaps a 'collection' of laments of the heart can only be its real self when it's 'scattered', when it refuses the conventional closure of the binding-thread and insists on the overpowering, anarchic force of its grief.

Also, the pages that are given to the wind are the pages

'of' the fragments of the heart. Does this mean pages that are about

the fragments of the heart, or that are by the fragments of the heart,

or that are the fragments of the heart (since after all varaq

can also mean 'slice')? The same questions arise in the case of the memorial

'of' the lament; we can't tell exactly what relationship exists between the

two nouns. Is is a monument that commemorates the lament, to keep its memory

green in the future? Or is it a keepsake retained by the lament itself, for

its own nostalgic recollection? On the poetically useful multivalence of the

i.zaafat see {16,1}.

Nazm:

He has given the pieces of the heart the simile of pages, then given the pages the simile of a bound divan. And the poet has supposed the lament to be something that has destroyed its own memorial. (19)

== Nazm page 19