FWP:

SETS == CATCH-22

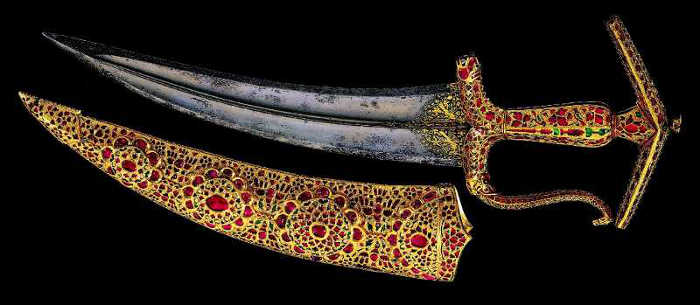

Raza 1995, p. 161 has baazuu , as does the Nuskhah-e Hamidiyah, c.1821, p. 77, while Arshi has ;xanjar . In this one rare case, I think Arshi's text is wrong. I am going with baazuu .

This verse and the two preceding ones all reflect on the lover's exhaustion and decay, and the inevitability of his death-- and yet how different they are. The first verse reports the dire situation of heart-loss flatly and abstractly; the second verse sees the lover's death as a routine occurrence, like theguttering of a burnt-out candle; the present verse sees the lover's death as something desirable that must be contrived and planned for.

The lover must contrive and plan for his death even though he's pretty far along on the road to it anyway-- he's so worn down that he's 'no longer fit' to be murdered by the beloved with her own hands. Obviously he had been hoping for that great honor-- which he seeks in {40,2}, wittily but with apparent sincerity and fervor-- but he has now had to abandon his hopes. Bekhud Dihlavi points out the 'catch-22' quality of his situation: she won't kill him because of his wretched condition, yet it's his wretched condition (in his mad passion for her) that makes him long for her to kill him. Thus even if she won't kill him, she's still invoked as the 'murderer'.

The lover addresses his own heart, and appeals for a way out. Because the heart is his best-- and, ultimately, only-- confidant? Because the heart was the one who particularly longed to be slain by the beloved? Because it is the heart that must now finish 'turning itself to blood', and thus free him from his wretched life? Or is addressing one's heart just a slightly formalized way of addressing oneself? These questions hover alongside those mentioned by Mihr, and add to the resonance of the verse.

Note for grammar fans: This is another case of the skewed

correlation between Urdu and English tenses (despite their seeming parallelism);

for discussion, see {38,1}. In English, considering

the grammar of the verse, we'd feel impelled to say 'I haven't remained suitable'.

Nazm:

That is, my state has become so altered that she considers me unworthy prey. (38)

== Nazm page 38