FWP:

SETS

BEKHUDI: {21,6}

SCRIPT EFFECTS: {33,7}

WRITING: {7,3}

The commentators explicate the most obvious reading: a boast of the speaker's superiority over Majnun. The speaker himself was already highly 'oblivion-instructed', or was even 'oblivion-instructing', or was finely copying or writing 'oblivion', in the lesson of 'self-lessness' (meaning not unselfishness but self-transcendence), at a time when Majnun was a mere schoolboy only beginning to learn the alphabet.

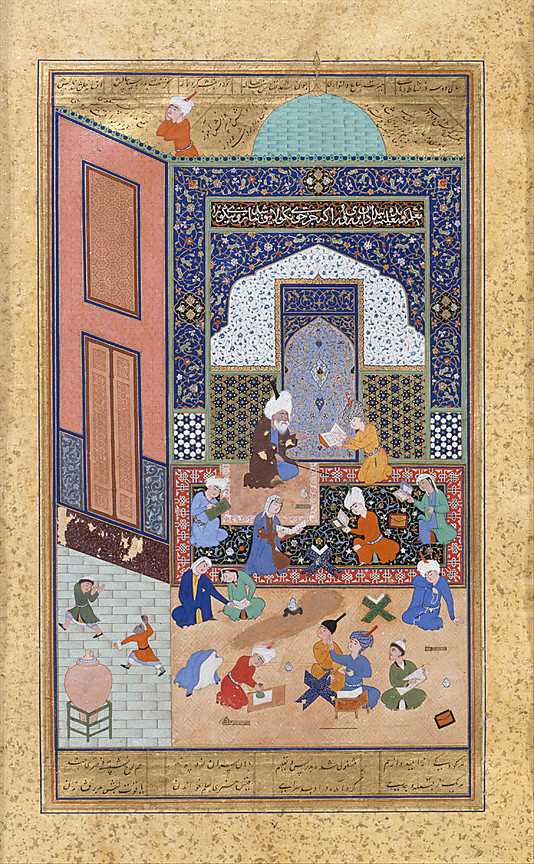

In the process of learning, Majnun used to write laam alif on the schoolhouse wall. If these two letters are joined, they become laa , a fundamental word: a negation meaning in Arabic 'no, not, without'. And if the two letters are taken as initiating two separate words, they stand for laa ill;aah , the beginning of the Arabic for 'There is no God [but God]', which is not only the start of the (Sunni) Muslim profession of faith, but also, as Bekhud Dihlavi points out, a Sufi mystical phrase.

But there's another possibility as well, because 'since that era' [us zamaane se]

can mean not only temporal sequence, but also an implied causality. It could

be that what made the speaker so 'oblivion-instructed' was in fact the sight of Majnun

writing laa on the schoolhouse wall. Was it the childish

Majnun's precocious mystical wisdom-- his choice of writing 'nothing' [laa]

instead of, say, 'a,b,c' [alif be]? Or was it the speaker's foreknowledge

of Majnun's emblematic fate that made the small boy's experimental scrawl so affecting and revelatory? Either way, it was from this sight that the speaker obtained instruction in oblivion.

Thus he reports this coincidence of events not as a boast of superiority over

Majnun, but as a tribute to the role he played-- perhaps unknowingly-- in the speaker's

own mystical education.

Nazm:

Both 'oblivion' and 'instruction' are fresh vocabulary, and the construction that joins both words is Persian-- that is, 'oblivion-instruction' has become an adjective referring to a person who has been instructed in oblivion. And this lesson which it has given is self-lessness. And the author has rejected alif be [A,B] in favor of laam alif [L,A] because when both letters are put together they become laa ['without'], which has an affinity with 'oblivion'. (60)

== Nazm page 60