FWP:

SETS == BHI; KAHAN; KYA

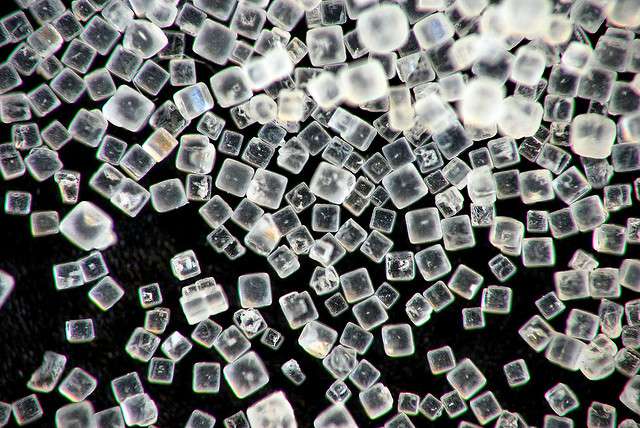

STONE: {62,5}

ABOUT salt and wounds: Conveniently, in English too we speak of 'rubbing salt in the wound' with the sense of deliberately aggravating the pain of a wound (or more generally, of adding insult to injury). Since the lover is half-crazed with the pleasure of pain, he often seems to welcome, or even long for, this addition to his suffering, as in the present verse. In the next verse, {77,2}, we see

also that 'salt' is nothing simple, but comes in varying kinds that

have varying value. Other verses about salt and wounds, in addition to those in the present ghazal with its refrain of namak : {4,7}; {17,7}; {61,4}; {146,5x}; {165,1}; {233,5}.

Well, this verse is an unusually clear-cut case. As far as I can tell, not one of the commentators mentions a single reading except (1a) and (2a). Every single later commentator whose work I'm using follows right along in Nazm's footsteps (including Bekhud Mohani, who simply interprets the boys as unpracticed beloveds).

But I will insist on the presence of all the other readings. I think hardly anyone will deny that all the readings are grammatically possible. Perhaps the commentators don't mention them because they're satisfied that they already have either the best, or the only legitimate, reading-- the one that they think Ghalib himself surely had in mind. But how sadly un-Ghalibian that attitude is!

If you've been looking at other verses in this commentary, you probably already know my general lines of argument. Ghalib has a tool-kit of special effects (many of which are illustrated in the SETS list) through which over and over again he demonstrates his remarkable genius for creating lines and verses with multiple, unresolvable meanings. In the absence of reason to the contrary, therefore, we should always LOOK for multiple meanings in a verse, so we can savor the pleasures of the multivalence that Ghalib so conspicuously created.

I don't at all reject (1a) and (2a), so I'll leave them as the commentators have them. Why might we want also to explore (1b)? Think of uses like 'what kind of friendship is this?' [yih kahaa;N kii dostii hai], in {20,5}. Even closer to that of the present verse is 'where/how might we go and test fate?' [ham kahaa;N qismat aazmaane jaa))e;N], in {26,3}. They are both negative rhetorical questions in a sense, but can also be real questions, and need not be wholly sarcastic ones. We can imagine a similar structure for 'how could/would the children sprinkle salt?' [:tiflaan namak kahaa;N chhi;Rke;N]. It might suggest the idea that they never could/would, but it also leaves a grammatical loophole for being explored, or even answered.

And that reading gives a whole new twist to the second line. How can we expect rock-throwing urchins to know the subtleties of passion or pain? How can they possibly provide salt for the wounds, even if they want to? And who wants them to? Here are some responses by the lover, implicit in the various readings of the second line:

=What would be the pleasure, if salt were in the stones too? It would be overkill! I don't need any more salt-- I have enough of my own already.

=Imagine my wanting salt from such careless little barbarians! I get salt for my wounds only from the beloved herself, who is supremely expert at providing it. (Though the Advisor does his best to provide some too; see {4,7} for a description.)

=What a disaster-- if salt were everywhere and easy to get, there'd be no honor in being a lover! (This line of thought follows the reasoning of {60,3}.)

=Everybody knows that salt has to be 'sprinkled' [chhi;Raknaa] on a wound, delicately, slowly, repeatedly, for maximum effect. How could careless children with their crude one-time stones possibly accomplish this?

=I wonder-- what in fact would it be like if salt inhered even in stones? Would that really be pleasurable, or not? I must consider the implications before deciding.

And so on; a bit of thought would no doubt reveal further possibilities. (Of course, it's fun to find your own favorites-- when you do, keep the double possibilities of the bhii in mind.) But surely these possibilities are enough to make the point. Wouldn't we rather have a richer verse than a poorer one? Wouldn't we prefer a multi-dimensional verse, rather than one that could be captured by a prose paraphrase?

For more verses about stone-throwing, see {35,10}.

Nazm:

The boys who are throwing rocks at the madman, and who don't think to put salt on the wounds-- what kind of intelligence do they have? If these stones were lumps of salt, it would have been a wonderful pleasure-- the wound would have been received, and salt too would have been sprinkled! (78)

== Nazm page 78