FWP:

SETS == GROTESQUERIE; MUSHAIRAH

Well, this one is pretty clear, and the commentators explicate it well. Among the other qualities of a good mushairah verse that the verse displays, it withholds its 'punch' word, sozan , till the very end.

As Bekhud Dihlavi observes, 'pleasure' [la;z;zat] has been used where we'd expect 'pain'. Which at once plunges us into the familiar vortex of the lover's pleasure-in-pain. In effect, the lover has been accused by the Other of un-lover-like behavior: of seeking the 'pleasure' of relief from pain, of a 'cure' [chaarah] for his wound. But instead, the lover claims to be seeking the 'pleasure' of more pain. This makes perfect sense to the lover, but the Other will never get it. This verse has a kind of fraternal twin in {171,2}.

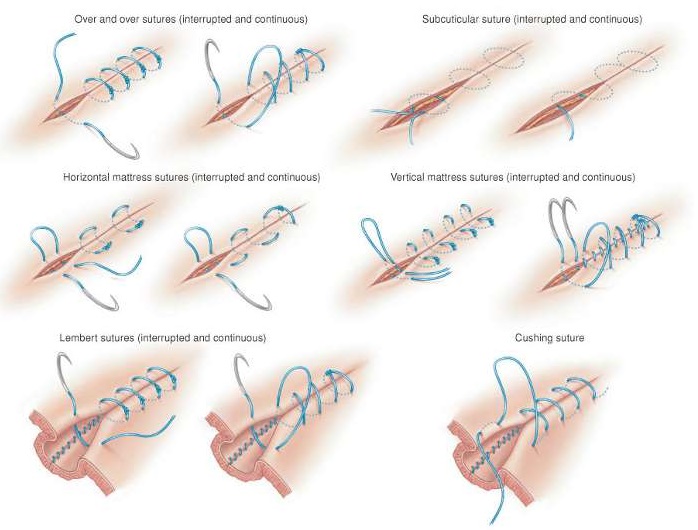

If we dwell on this verse too minutely, it definitely becomes a candidate

for the 'grotesquerie' category. Do we really need to imagine the

process of stitching up a wound, in all its gory and painful detail? Does

it really work, poetically, to make us consider the way the heavy needle is

plunged again and again into the torn flesh, so that it creates, as Bekhud

Dihlavi points out, what amounts to a whole series of fresh wounds with a

sharp new dagger? To me, this verse is right on the borderline of being too

graphic and grotesque to be fully effective.

Nazm:

That is, the use of a needle in the wound is not in order to to cure it, but in order to obtain the pleasure of the wound of the needle. The theme is that of a former verse, but the author has here doubled its beauty by giving it the simile of the Rival's misunderstanding. (86)

== Nazm page 86