FWP:

SETS == HUMOR

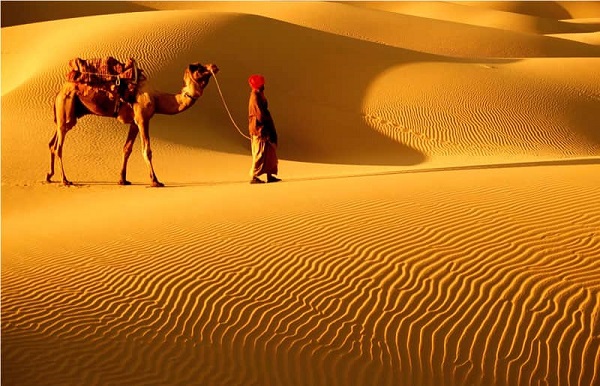

DESERT: {3,1}

HOME: {14,9}

The colloquial use of ma((luum as a vigorous negative exclamatory marker is very common; for more on this see {4,3}.

In classical mushairah oral-performance style, this verse presents a first line that is like a riddle. It can't be reliably interpreted without more information-- but we're enticed to guess at it. When after a suitable interval of suspense, we get to hear the second line, what a delightful, witty punch it carries!

Just consider the levels of implication. The first line is a parody of the kind of thing people say when they are house-hunting. (For a verse with a similar thoughtfully comparative tone, see {101,9}.) 'Well, that one was just as nice as this one, but it had no closet space at all!' In proper comparative mode, the line mentions first a virtue, then a defect. But what is the virtue? Amusingly, as the lover is critically comparing possible dwelling places, he's analyzing their relative degrees of ruinedness, desolation, and general misery. Yes, he says approvingly, the former one was just as ruined as my present one, there's nothing to choose between them in that regard. But when it comes to space, to scope, to spread-out-ness! His old house was terribly cramped, and this present one gives me all the amplitude that even he could desire.

By implication, we see the lover's values: he prefers a dwelling as ruined and wretched as possible, and as spacious as possible-- no doubt so that he can roam freely in his restlessness, and behave madly in solitude without being bothered by neighbors. The final touch of wit is his praising the 'luxury, enjoyment' [((aish] that he has in the desert. So far from finding the desert inconvenient in any way, he thinks it a five-star hotel. Which of course reminds us of his desperation and his mad passion; ultimately, he wants nothing at all from the world except to be out of it. He has so little regard for worldly comforts or luxuries (or even perhaps so little knowledge of what they're like) that he declares the desert to embody them.

But of course, what kind of vuh ((aish does he really have in the desert? A kind that causes him to forget his home entirely. We may at first think of that as high praise, but then we think again. Is the desert perhaps not a paradise, but merely a place for amnesia and loss of self? Does he even remember what a home is? Could loss of memory be the reason he considers the desert life luxurious? The layers of implication and ambiguity are rich, but the idiomatic, colloquial punch of the verse keeps it lively and amusing.

This verse has a beautiful, perfect, irresistible companion

verse in {35,8}. They orbit each other like

spectacular twin stars.

Nazm:

That is, the house itself is desolate like the desert, but how can it have as much scope? (107)

== Nazm page 107