FWP:

SETS == AUR; BASKIH;

WORDPLAY

CHAK-E GAREBAN: {17,9}

In line one, as so often, the use of baskih generates the two meanings of 'although' and 'to such an extent', both of which are relied upon by the commentators. The positioning of aur also conveniently means that it can be used to suggest 'more', or 'other[s]', or 'and'.

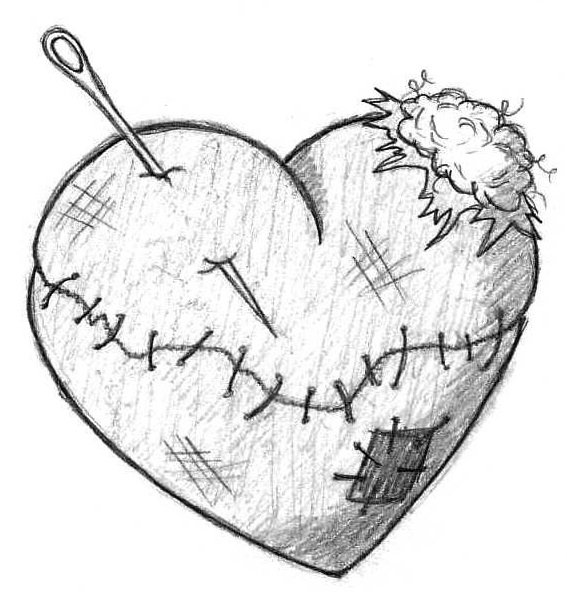

The wordplay in this verse is a treat: 'sewing' [ba;xyah] and 'tearing' [chaak] are bumped up right against each other; as Faruqi notes, sighs too are often poetically constructed as either sharp like needles, or connected like a thread. Above all, as Nazm points out, the punning on 'to sew'-- siinaa , suggested by siinah or 'breast'-- is marvelous icing on the cake.

As the commentators make clear, there's such a range of readings possible! Does the 'sewing-up of the rip in the collar' by the sighs constitute an actual sewing-up, or merely a warped parody of it that in fact worsens the situation? Does the lover seek out, or control, or desire this special form of 'sewing-up', or does he suffer under its onslaughts? Does this 'sewing-up' increase the lover's madness, or diminish it, or merely show its steady-state endlessness?

However we view the implications of the process, it seems to be one that, in principle, can go on forever. In that sense the verse evokes {19,1}, in which the fingernails gouge out a wound, and are then forcibly trimmed; the wound heals, the fingernails grow back, and the whole cycle starts again. But the ambiguous 'sewing-up' makes this verse more complex. Do the speaker's sighs, and his suppression of them, really constitute any kind of 'repair' of his torn collar?

It could also be that this process is the (so-called) 'stitching-up' of the the collar

only in the sense that the collar won’t get any other stitching-up than this.

Think of {17,9}, after all; and of another,

more despairing verse about stitching things up, {113,1}.

Nazm:

In this verse, he has given for the welling up of sighs again and again, and their suppression again and again, the simile of stitching; that is, a moving thing is the simile of a moving thing, and the cause of similitude is movement. But for a sigh, such movement is only a poetic supposition. For this reason, this simile is not really eloquent [badii((] the way other such verses are that have passed by. And with regard to theme, the verse is meaningless. Persian and Urdu poets compose such themes with their eyes closed. Here, the .zil((a he has said of ba;xyah and siinah is not devoid of pleasure. (119)== Nazm page 119