FWP:

SETS == KIH

MIRROR: {8,3}

ROAD: {10,12}

I translate rahnaa as 'stay' or 'remain', rather than 'live', because it's not clear how long the speaker will be allowed to stay in the beloved's street. But what can account for the odd rhetorical question in that first line? The speaker seems to be rejecting, perhaps a bit indignantly, some suggestion that he might have 'remembered' how to remain in the beloved's street. Does he reject the suggestion because he'd never been presumptuous enough to be there before, and thus wanted due credit for his humility? Or does he reject it because of his self-lessness, which rendered him oblivious (as in the previous verse, {116,7}) to all merely formal details? Or is he just generally emphasizing his cluelessness, his haplessness, his need for guidance?

Moreover, what kind of thing is the style/character/state [va.z((a] that he doesn't remember? The term often suggests a kind of personal dignity that must be upheld at all costs; see the discussion of it in {115,7}. In that verse, paas-e va.z((a is something that prevents the speaker from falling below a certain standard of dignity merely in order to meet the beloved on the street.

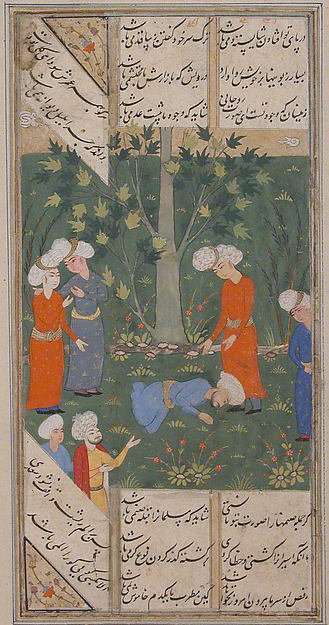

Here, va.z((a is something to be (re?)learned afresh, with no preconceived notions, and it seems to have no (overt) connection with dignity. It is to be learned from the footprint. In the ghazal world the footprint, by virtue of its shape, resembles (and thus becomes) a mouth perpetually open in amazement; as Nazm and others also point out, the footprint also lies flat in the dust, as humbly as it possibly can. In both these respects it presents a model for the lover, showing him the 'style' he must adopt. The footprint could very well be his own footprint: the very first step he takes into the beloved's street perhaps already teaches him the local protocol (or survival tactics).

It's easy to see why the footprint could be a 'mirror'-- by virtue of its shape, and also because the mirror too is often full of amazement (as in {63,1}). For more on the nature of ;hairat , see {51,9x}. But why is the footprint's amazement here a 'mirror-possessor' [aa))inah-daar], rather than simply a mirror? It's easier to ask the question than to answer it.

For another perspective on the footprint as model for behavior

in the beloved's street, see {123,1}.

Nazm:

The footprint showed me that in this way, mingled with the dust, and struck with amazement at the glory/appearance of beauty, is the way one ought to live in the beloved's street. (125-26)

== Nazm page 125; Nazm page 126