FWP:

SETS == EXCLAMATION

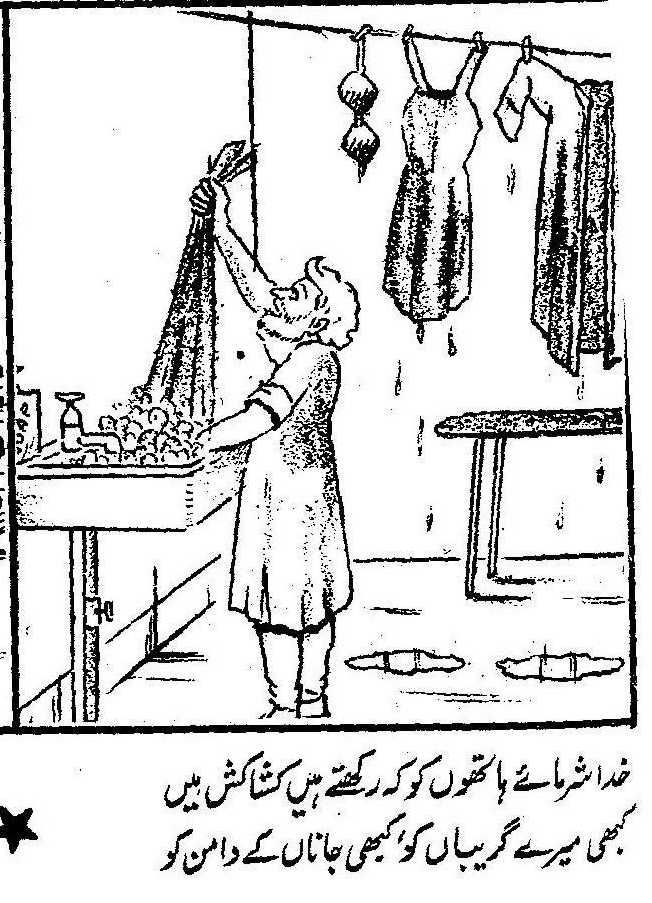

CHAK-E GAREBAN: {17,9}

SHAME/HONOR: {3,5}

As Bekhud Dihlavi observes, it's amusing how virtuously the speaker denounces the shamelessness of those evil hands! (Just as though he were not hopelessly attached to them.) 'May the Lord bring shame upon them', he exclaims. Which is a self-fulfilling prophecy, since they're engaged in scandalous behavior that will bring shame upon them in the normal course of events, even without any divine intervention.

Is the Lord being asked to bring shame upon them in the eyes of others-- finger-pointing, gossip, a humiliating public scandal-- to punish them? Or should they be subject to shame in their own eyes (!)-- giving them a 'sense of shame'-- so that they'd be moved to behave better?

And what exactly is the shameful part? Tugging on the collar? Tugging on the beloved's garment-hem? Tugging on both in turn? Or keeping on tugging (on any or all of these), when the limits of propriety have already been exceeded?

Or maybe 'tugging' itself isn't the real issue, or is only part of the problem: consider all the other possible, and variously and enjoyably relevant (why are we not surprised?) meanings of kashaakash (see the definition above).

Good verses for comparison: {106,1} and {106,2}.

(by Wahab Haidar)

Nazm:

That is, at the time of leave-taking, her garment-hem; and in the state of separation, my collar. (128)

== Nazm page 128