FWP:

SETS == BHI; SUBJECT?; WORDPLAY

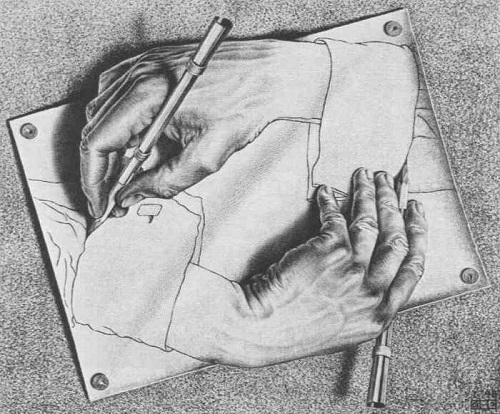

By great good fortune (or some kind of common human metaphor-making process?) we have almost the same idiom in English as the one on which this verse is based. To us, 'to draw' means, among other things, both 'to make a picture' and 'to attract', just as khe;Nchnaa does in Urdu (with its intransitive counterpart khi;Nchnaa meaning both 'to be drawn [as a picture]' and 'to be attracted', in a way that has no real counterpart in English). This shared metaphor means that the enjoyableness of the verse can be experienced more directly, and not through laborious explanations. The subtle effect of the tiny monosyllable bhii -- with its double reminder both that others are similarly affected, and/or that the artist is, or should be, in a class by himself-- is a further delight.

And what a masterpiece of versatility the second line is! Its two clauses both apply to a masculine singular, unspecified subject, in a way that's perfectly idiomatic in Urdu. And the first line cleverly provides two such subjects, the picture and the painter. All four permutations are entirely possible, and quite meaningful: he/he, it/it, he/it, and it/he. The fact that the various permutations only create dizzying variations on the same basic idea is an additional pleasure-- since that's what the verse is saying, after all: that 'drawing' and 'being drawn' are, in this case, inseparably intertwined.

Another reading is pointed out by Vasmi Abidi (Jan. 2005), and I think at least some of the commentators share it (though it's hard to tell in some cases, since mostly they just paraphrase the verse itself). Vasmi points out that in {205,2} the second line, kih jitnaa khe;Nchtaa huu;N aur khi;Nchtaa jaa))e hai mujh se , clearly uses khi;Nchnaa to mean 'draws away' (as is established by the se ). As Vasmi observes, the same reading could certainly apply to this verse. I agree, and I've incorporated this reading as (2b). The enjoyable part is that the naaz of the beloved's image can easily have both effects: to draw someone in, and at the same time to (coquettishly) draw itself away from him. And the first line in fact gives us a strong hint in this direction, by exclaiming at kyaa kyaa naaz , which makes it clear that more than one kind of naaz is involved.

For the (very few) otherexamples of verses about drawing or painting, see {6,1}.

Nazm:

That is, the way the painter 'draws' her picture, to that very extent the picture too 'draws' him. And this [second] 'draw' has a different meaning. (165)

== Nazm page 165