FWP:

SETS

GATHERINGS: {6,3}

WARNINGS: {15,15}

This is the fourth verse of a seven-verse verse-set; for discussion of the whole verse-set see {169,6} (and for discussion of the 'spread' as well).

The introductory yaa that seems so peculiar is meant to correlate with its partner at the beginning of {169,11}. The two make a contrastive set [yaa yih , yaa vuh] not exactly of mutually exclusive alternatives, but of two highly contrasted moments in time: if we look at night, it's this; if we look at dawn, it's that. (As an example, Asi uses the yaa yih , yaa vuh construction unselfconsciously in his discussion of {40,5x}.) The dekhte the makes the looking a past habitual action, presumably by the speaker himself (using ham ).

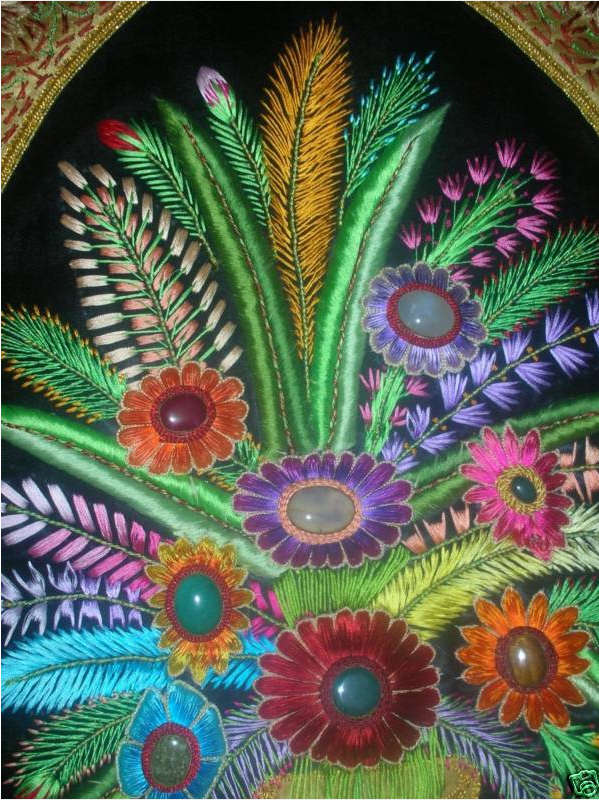

The gardener gathers up the hem of his garment in his hand, to make a sort of hammock in which to carry a great mass of freshly picked flowers, in a huge piled-up heap. By contrast, the flower-seller offers quality rather than quantity: a mere handful or small bouquet of the most exquisite blooms, carefully chosen and arranged to appeal to the connoisseur. Thus what the line is 'really' saying, in the heresy of paraphrase, is that the gathering is as full as possible of the radiance and perfume of gloriously fresh flowers. (As we in the ghazal world are always aware, the beloved herself is the ultimate 'rose'.)

But of course, the flowers are never mentioned-- which has several advantages. First, it makes the reader work a bit, which creates a buzz in the brain that is enjoyable in itself. And second, it has the advantage of smuggling in people (the gardener, the flower-seller) who are lowly servants-- if even they are (implicitly, metaphorically) there, how crowded and lively the gathering must be! Ghalib has thus effortlessly peopled his 'spread' and given it the requisite 'brilliance' [raunaq] that a fine party must have. (Compare the possible presence of the pearl-seller in {169,4}.)

In our tour of the senses, we've had eyes and ears, the taste

of wine for the tongue, and now, with all those gorgeous flowers, we add some delights for the sense of smell.

Nazm:

[No comments on this particular verse.] (190)

== Nazm page 190