FWP:

SETS == IDIOMS; REPETITION

SOUND EFFECTS: {26,7}

SPEAKING: {14,4}

Here's a well-known and very popular ghazal. Because of its refrain, the whole ghazal is greatly shaped by idiomatic expressions involving baat ban'naa , often with the baat colloquially omitted (for another example of the same idiom, see {70,3}. The present verse also features the especially suitable baat banaanaa (see the definition above), made from the transitive form of the same verb. In addition, the second line of the verse cleverly integrates baat banaanaa into another common idiomatic pattern displayed in banaa))e nah bane ; for discussion of this structure, see {191,8}.

The result is a classic second line with almost tongue-twisting sound effects, a wonderfully circular feeling when you recite it, and a kind of radical untranslatability. The framing structure kyaa bane baat jahaa;N baat ... nah bane [how would a thing succeed, where a thing wouldn't succeed?] can hardly fail to be present in our ear and mind, interrupted only by banaa))e , which itself works, in terms of both sound and idiomatic meaning, as a kind of embellishment of the theme.

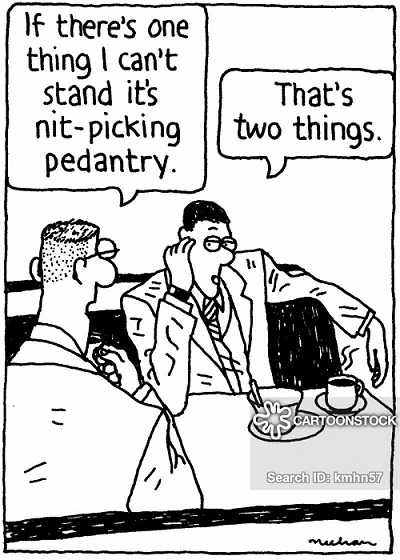

What exactly is the problem being expressed in this inshaa))iyah second line? Basically, that the beloved is a nit-picker, so the speaker can't get anywhere when he talks to her and tries to tell her the 'grief of the heart'. But the precise involvement of falsehood versus truth remains undecideable. Here are some possibilities:

=She's a nit-picker-- thus she detects and unravels the grandiose falsehoods with which the speaker tries to impress her, so that his situation is hopeless.

=She's a nit-picker to such a degree that not even carefully framed fancy falsehoods would impress her, so what hope is there for a helplessly truthful, inarticulate, suffering lover like the speaker?

=She's a nit-picker about style, and only enjoys fancy rhetoric and floridly embellished verbiage-- and even that doesn't ultimately succeed with her, so what hope can any lover have?

Ajit Sanzgiri has suggested that the 'nit-picker' can be the 'grief of the heart' itself-- it is strict and scrupulous, and refuses to be embellished or rhetorically dressed up in any way, even to please the beloved. I think this is possible, but not as persuasive as the primary reading, since personifying the 'grief of the heart' is not very common in itself-- much less envisioning it as a 'nit-picker' (which is the obvious and perfect behavior for the beloved). But who can say that this reading too doesn't hover at the edges of the main meaning, especially in view of the positioning and grammar of the first half of the first line?

This one is really a verse of convoluted idiomatic wordplay,

and its great charm is the astonishing second line. The following verse, {191,2},

has a similar structure.

Ghalib:

[1862, to Ala'i:] [In a letter, Ghalib quotes {191:1, 2, 5, 8, 4, 9}. For the letter, see {161,1}.]