FWP:

SETS == REPETITION; SUBJECT?

SOUND EFFECTS verses (some notable examples): {4,3}; {20,7}

(internal rhyme); {20,10} (internal rhyme);

{21,13}; {26,7}; {31,3};

{34,1}; {41,6}; {42,4};

{47,2}; {48,5};

{51,8x}***, spectacular; {54,3};

{57,11x}; {58,7}; {58,9};

{59,4}; {61,6}; {62,2}; {62,9}; {64,3};

{82,1}; {85,4};

{86,7}; {89,3}

(criticism); {90,5}; {91,3};

{91,7}; {91,10};

{91,13x}; {92,3}; {96,1};

{96,3}; {97,13};

{99,3}*; {107,6};

{111,1}; {111,9};

{113,7}; {115,3}

and {116,3} (internal rhyme); {116,7}

(wind sound); {123,10} ( shahr and shi((r ); {127,1-3};

{132,8x}*; {147,5x}; {147,6x}; {149,3} ( rah-e and rahe ); {151,2}; {151,4}; {158,4};

{166,1}; {173,10};

{178,5}; {181,2};

{184,1}*; {183,5}

(semantic); {188,4x} ( paimaan and paimaanah ); {191,1}; {194,6};

{199,3}; {200,3}; {209,4};

{228,8} (homonyms); {203,2}; {212,3}, 'dental' d ; {215,3} // {261x,1}; {283x,5} (4 times, jahaa;N ); {335x,3} ( aa;N-suu and aa;Nsuu ); {349x,1}* (gzl with maximum internal rhyme); {352x,4} ( aa))iinah and aa))iin-e ); {360x,7} ( saaqii and baaqii ); {373x,1}; {385x,3}, Persian verbs; {405x,6}, pa))e and paa-e ; {423x,4}, ;xudaa ya((nii ; {436x,4}, 2 sets

I chose this verse for unusually full treatment because it shows particularly clearly some of the problems and deficiencies of the commentarial tradition. Even a person who didn't know Urdu would notice at once, on hearing this verse, that in the first line every word except one rhymes. This makes this line unique in Ghalib's divan. Perhaps one might not even care for the effect, but an effect it certainly is; Yet not one commentator so much as acknowledges that it exists.

Instead, the commentators devote themselves, as usual, to producing a prose paraphrase of 'the meaning' of the verse. Most of them are indeed reading the first line in two different ways at once, whether or not they are aware of it: in their commentary the meanings I have called (1a) and (1b) are blithely and unreflectively interwoven. The only reason they can read this line in two different ways is that Ghalib has carefully constructed the grammar so as to make the two readings both possible and inescapable (that is, there's no way to rule either of them out). Yet none of the commentators acknowledge this poetically significant fact, or help the reader to reconstruct the two different analyses of the grammar that generate the different meanings.

If we move on to the second line, we find the commentators equally unhelpful. Even someone who didn't know Urdu could tell on hearing the line that ;haq was being emphatically repeated, in metrically conspicuous positions, so that special attention was being called to it. Ghalib is clearly bouncing us around in its various meanings of 'truth' and 'justice' and so on, requiring us to reflect on the various senses of ;haq (see the definition above). Yet Nazm helps us only by high-handedly defining away the problem (and the pleasure). The others ignore it, except for Shadan who actually rewrites the line, suggesting that sach could well have been used to avoid the confusion!

Just as none of the commentators acknowledge the conspicuous display of rhyme in the first line, so none of them acknowledge the central and obviously deliberate wordplay (and, importantly, meaning-play) with ;haq in the second line. For another example of the ambiguous use of ;haq , see {64,1}.

The result is, if you believe the commentators, a bland piece of religious piety. Poor Ghalib! How he would have hated such blindness to his elegant and carefully-wrought devices! Why are the commentators so singularly unhelpful? Nobody can give an authoritative answer. I have written a somewhat speculative paper ('The Meaning of the Meaningless Verses') about this; it is available here.

In the meantime, let me briefly give my own comments on this verse. I think the first line as (1a) and (1b) is a delight, with the two meanings not contradicting each other, but somehow engaging in a kind of tug-of-war. Making the words rhyme seems like something that perhaps began to happen by accident-- since stripping out chunks of grammar to create ambiguity would easily produce a sequence of feminine endings agreeing with jaan -- and that he then continued just because he could, out of the sheer delight of virtuosity, in order to surprise and amuse his audience by offering many pleasures at once.

I would also propose another way of reading the second line: the ;haq , the 'claim' or 'right', that didn't get fulfilled could also have been the beloved/God's duty toward us. If the lover gives his life (1a), and the beloved or God considers that it's hers/his already, the lover doesn't get any credit for his sacrifice. Is that fair, is that according to his claim or his right? The truth is, it's not.

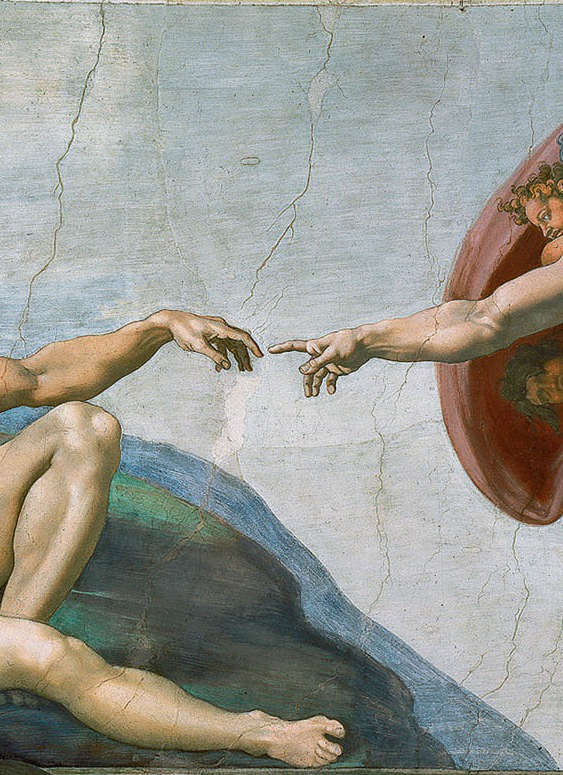

Similarly, if God gives the speaker life (1b), and retains ownership of it the whole time, so that it's really always usii kii , 'only/emphatically His' -- is that fair or just? The truth is, it's not. God has only pretended to give it, while actually it remains beyond the speaker's control. This complaint of the helplessness of humans in a world over which they have no power is vintage Ghalib: it is exactly the point of {1,1}. And it's echoed in Ghalib's letter quoted above.

Compare the unpublished {424x,7}, which similarly plays with questions of ownership of the self, and which might even be read as accusing the Lord of a veiled form of 'self-worship'.

Compare Mir's similarly complex exploitation of the possibilities of ;haq : M{1059,2}; and his even more radical enjoyment of the possibilities of sheer wordplay: M{1836,6}.

Ghalib:

[Sept. 1862, to Majruh:] We hear that in November the Maharaja will be granted authority [i;xtiyaar]. Indeed it will be given-- but that authority will be of the kind that the Lord has granted to his creatures: He has kept all the power in his own hands, and caused human beings to be blamed/disgraced.

==Urdu text: Khaliq Anjum vol. 2, p. 537