FWP:

SETS == BHI

IDOL: {8,1}

RELIGIONS: {60,2}

The wit and pleasure of this verse lie in the cleverly chosen word nisbat . Its Arabic root, nasab , means 'genealogy; lineage, race, stock, family, caste' (Platts p. 1137). And among the meanings of nisbat in Urdu are very common and prominent ones that involve just such a sense of family ties: 'relationship by marriage', or a 'kinsman' ('relation, connexion', in Platts's English usage).

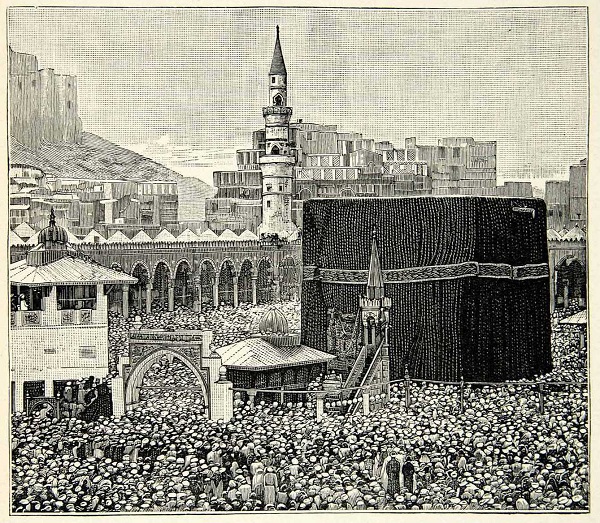

According to traditional Muslim accounts, many pre-Islamic idols were removed from the Ka'bah by the Prophet's command, and at least some of them were goddesses. Does this mean that these idols were formerly members of the Ka'bah 'lineage' or 'family', but then were banished from the family? If so, it's tempting to imagine that they were banished for some kind of bad behavior. We all know that the 'idols' of the ghazal world, the beloveds, are willful, arrogant, and perhaps less than chaste. Does that mean these idols/beloveds, despite their unacceptable behavior, still have some kind of Divine blood in their veins? Is there still perhaps some kind of grudging recognition by the Lord of the Ka'bah, of their 'distant' kinship?

The clever use of bhii also provokes us to make comparisons. Plainly the idols referred to in the verse are the ones who used to live in the Ka'bah, like Lat and Manat. The bhii invites us to compare them to other idols (surely the beautiful beloveds) who apparently have a better-known and more indisputable 'distant relationship' with the Ka'bah. Either 'even' Lat and Manat (members of an exceptional group) have such a relationship, or else Lat and Manat 'too' (unexceptional members of a larger group) have such a relationship. In either case, the relationship is defined with reference to that of other distantly-related idols (the beloveds) who apparently didn't undergo expulsion from the Ka'bah. So we come back to the question of what kind of a 'distant relationship' the beloveds in fact have with the Ka'bah. Needless to say, it's left for us to imagine. Playing with such thoughts is just the kind of 'mischievousness' [sho;xii] that Ghalib so often enjoys.

Less mischievously, the reference can also be one of philosophical or theological meditation: what in fact is the relationship between the true God and false pretenders to divinity? This is a general question, and also a particular one. The Ka'bah was apparently genuinely sacred in some very real sense even before the idols were expelled from it; otherwise, the need to expel the idols would hardly have been so pressing. So if the false idols were parts of a true holy space, does that give them any kind of a claim on it? Were they mere interlopers? The word nisbat , and the ongoingness of the relationship, suggest something more; but as so often, Ghalib leaves it for us to decide exactly how much more.

Compare {100,10x}, a verse about nisbat of an even closer kind.

Note for grammar fans: Arshi doesn't give any diacritical information that would help us distinguish un from in . Some editors, including Hamid, choose in . I prefer un because the reference is clearly to those idols who were expelled from the Ka'bah, and there's no particular reason to bring those idols into close proximity to the speaker. The verse then playfully uses 'those idols' as a way to highlight the situation of 'these idols', the beloveds, who are brought in only through the bhii .

Another note for grammar fans: In his commentary on {231,3},

Ghalib points out, 'Notice that [in {231,6}] pah is

short for par , with the meaning of 'but'.'

It's somewhat surprising to see such an observation, because really, in the grammatical context of the first line, what

else could it be? There's no possible object around, so it's hard to believe that anyone would take it for a postposition. Is Ghalib assuming that his correspondent is an exceptionally

unskilled reader?

Ghalib:

[See his comment in {231,3}.]