FWP:

This is the middle verse of a three-verse verse-set; for general comments, see {123,9}.

The tone seems casual, easy, superior; perhaps the speaker is chatting with some other travelers, in a bored and leisurely way, about his plans. Plainly he is the monarch of all he surveys. Is he deprecating Lucknow, by implying that it's just a casual way-station on the road to the holy places, and thus not worth a visit in its own right? Is he deprecating the holy places, by implying that they're just places for casual sightseeing, like Lucknow only a little later in the itinerary ('if it's Tuesday it must be Najaf')? Is he deprecating Najaf, which merely gets a 'tour' [sair], as opposed to the Ka'bah which gets a 'circumambulation' [:tauf]? Is he deprecating the 'circumambulation' too, by combining it casually with minor, trivial kinds of sightseeing?

And since he has already said in the previous verse that he has very little interest in (or esteem for) mere 'touring' or 'spectacle', is the whole rest of his journey destined to be as dubious as his visit to Lucknow? (To call it a 'sequence of ardor' after the previous bored and indifferent verse does sound a bit strange.) After he's seen the rest of the itinerary, will he still be vaguely wondering why he ever undertook such a trip in the first place? As so often, it's all in the tone, and ultimately we have to supply much of the tone ourselves.

This verse also offers a remarkable and witty bit of sound-play between the word shahr , or 'city', and shi((r , or 'verse'. While they don't sound identical, they nevertheless sound quite similar (especially in this position where the shahr is really meant to sound metrically almost like a single long syllable), and the prominent use of maq:ta(( , a term for the closing-verse of a ghazal, at the beginning of the line alerts us to expect some related bit of wordplay. We're not expecting sound-play, so there's an extra little treat in the shock of recognition.

Moreover, to say 'it's not the closing-verse' is enjoyable in itself: it's literally true (there's one more verse yet to come), but it also heralds the fact that the 'sequence of ardor' constituted by the ghazal-- and Lucknow-- is almost over. The next verse will in fact be the closing-verse of the verse-set, and of the ghazal itself-- and of Lucknow, since 'a hope/expectation' will carry the speaker far beyond it.

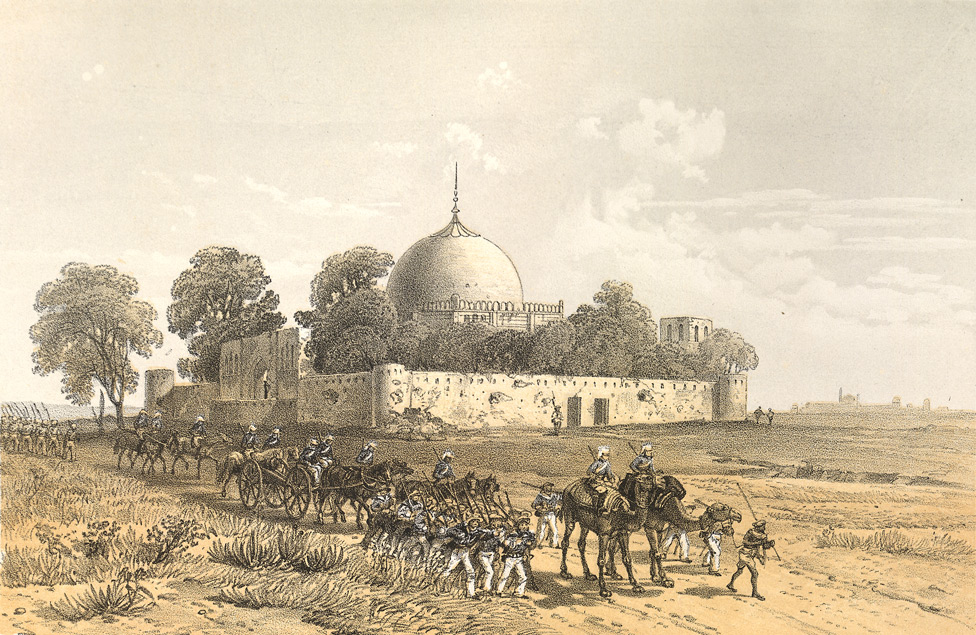

Veena Oldenburg comments (May 2006), 'A more historical explanation might be that Ghalib did not like the tawdry replica of Najaf and Karbala made by Ghazi ud-Din Haidar in his Shah Najaf, which later became his tomb. This was built around 1813-16 or thereabouts. Everyone gets a bit upset with the pretentious stuff the Navabs did-- and perhaps that's what he's saying about Lucknow.'

Here's Lucknow's own 'Shah Najaf', as it looked around 1860:

Nazm:

[He comments on the whole verse-set at {123,9}.]

== Nazm page 132