FWP:

SETS == KYA

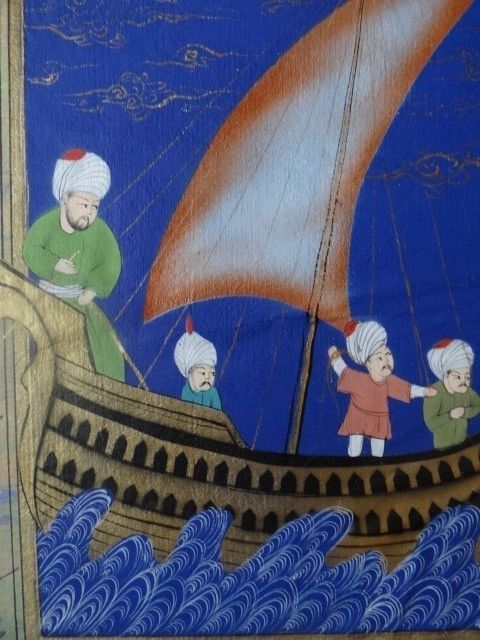

Here is a superb example of the delights of kyaa . The second line offers three possible readings. Since the ship has now reached the shore,

=Will you tell the Lord about the captain's cruelty and oppression, or won't you? There might be good arguments on both sides, and you'll have to think about it before deciding (2a).

=What! You will tell the Lord about the captain's cruelty and oppression?! Surely not! What's past is past, as the commentators observe, and why hold a futile grudge? Moreover, as Bekhud Mohani points out, the captain did after all fulfill his main task by getting you to shore (2b).

=How you will tell the Lord about the captain's cruelty and oppression! You will really give the Lord an earful! In the middle of the voyage, it's hard to judge these things rightly, or to anticipate how things might look tomorrow. And the captain can be very frightening. But now that you've arrived, you can safely report to the Lord how the captain had tormented you.

Needless to say, all three readings work most enjoyably, in their different ways, with the first line. The classic metaphor of life as a voyage, and death as arrival, hovers obviously around the verse, but of course it's not explicitly invoked; it's up to us to introduce it if we care to. Arrival is usually a good thing, especially after a long and difficult voyage; but arrival-as-death may be a more ambivalent state.

The wordplay of ;xudaa and naa-;xudaa is even richer than is first apparent. For though the naa is unquestionably derived from naav , 'ship', it also looks exactly like a negator (as in naa-in.saaf , 'injustice', or naa-ummiidii , 'hopelessness'). Thus overtones of a 'God' and a 'non-God' also seem to hover over the second line. Should one complain to the Lord about the activities of such a figure in the world? Does the Lord know already? Does the Lord want to hear about it? Is it perhaps beneath one's dignity even to mention it?

On the flexibility of jab kih , see {53,8}.

Nazm:

That is, if someone would have done evil, and that time would have passed, then one ought to forget about it, and not keep it in the heart. Luqman [a figure somewhat like Aesop] has summarized the wisdom of morality in four things:... two things are to be remembered: the coming of death, and the Lord's being present and all-seeing; and two things are to be forgotten: to have done some kindness to somebody, and somebody's having done some evil. (238)

== Nazm page 238