===

1328,

1

===

=== |

|

tark-e libaas se mere use kyaa vuh raftah ra((naa))ii kaa

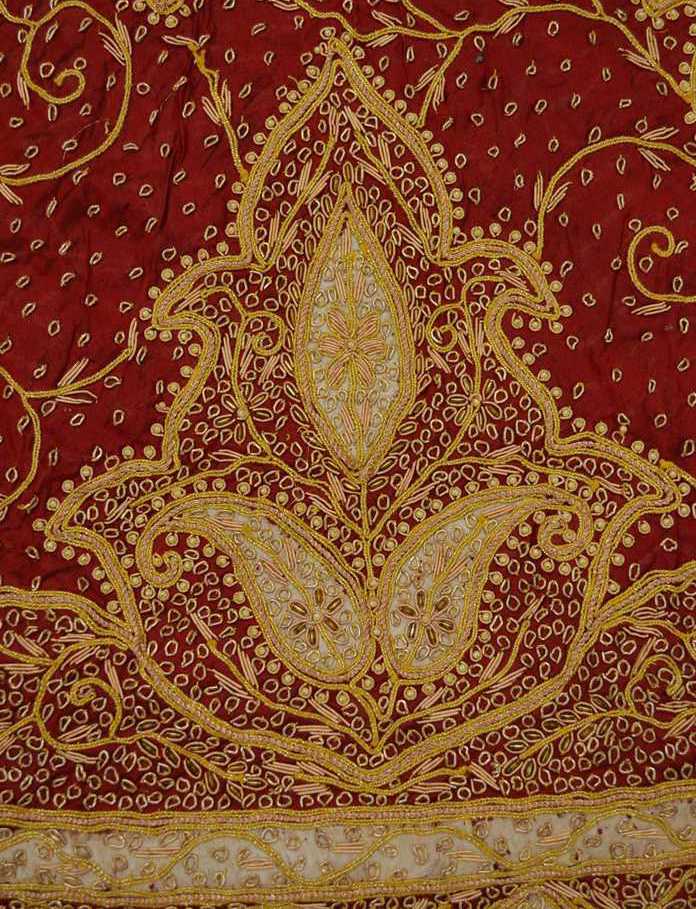

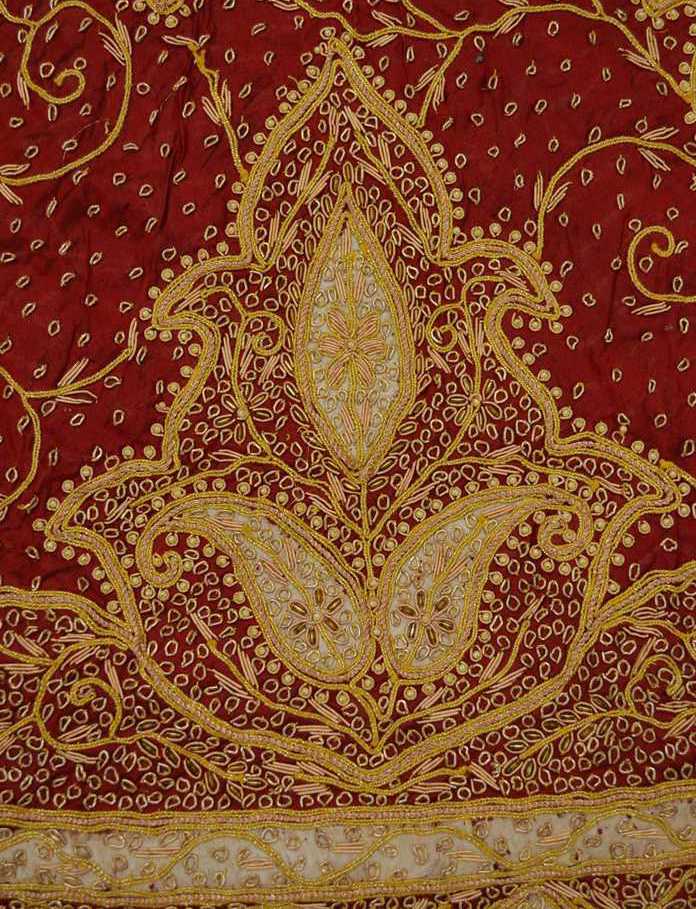

jaame kaa daaman paa))o;N me;N uljhaa haath aa;Nchal iklaa))ii kaa

1) as for my abandonment of clothing, what does she care? --she is absorbed in graceful-movement

2) the hem of her robe is entangled with/'in' her foot; her hand, [with/'in'] the embroidered-fabric border

ra((naa))ii : 'Gracefulness of motion, graceful gait; grace, loveliness, beauty'. (Platts p.595)

aa;Nchal : 'The border or hem of a cloak, veil, shawl, or mantle; a kind of sheet or wrapper'. (Platts p.89)

iklaa))ii : 'Singleness; loneliness; —a sheet of one breadth (generally laced)'. (Platts p.66)

FWP:

SETS

MOTIFS == CLOTHING/NAKEDNESS; EROTIC SUGGESTION

NAMES

TERMS == OPPOSITIONNote for grammar fans: The omission of me;N in the second line is worth noticing. No doubt Mir feels that he can omit it because it's (implicitly) part of a second clause that is meant to be parallel to the first clause in the line, which does contain its own me;N . But if we hadn't intuited that (or had SRF to point it out), it's easy to imagine that in this or some other case we could have found the grammar absolutely impenetrable-- especially since haath is unmarked, so there's absolutely no grammatical trace of the missing postposition. The possibility of this kind of thing just adds to the repertoire of interpretive tools that we need to carry with us into the Mirian world. These tiny little poems can be the hardest things in the world to interpret.