FWP:

SETS == A,B; IDIOMS

DREAMS: {3,3}

For background see S. R. Faruqi's choices. For more on Ghalib's unpublished verses, see the discussion in {4,8x}. This verse is from a different, unpublished, formally identical ghazal,, and is included for comparison. On the presentation of verses from unpublished ghazals like this one along with formally identical divan ghazals, see {145,5x}.

Thanks to the excellent scholarship of C. M. Naim, Sean Pue, and Hajnalka Kovacs of the Urdulist (June 2009), it's been established that the 'vein of sleep' [rag-e ;xvaab] is a well-attested Persian expression referring to a vein in the body that will, if pressed, put the person to sleep-- or, by metaphorical extension, will cause the person to surrender and become helpless and submissive.

This is an 'A,B' verse, in which the two lines are semantically quite independent and it's up to us to figure out how they're connected. The first line offers what appears to be a general truth, though slightly attenuated by the subjunctive: that love 'would know' how to understand, and/or how to make, a 'graft' onto the 'plant of affection'. We're expecting the second line to give us a more specific illustration of this process.

And indeed we get such an illustration-- but is it a positive one (in which love manifestly does know), or a negative one (in which true love 'would know', but some kind of flawed love wouldn't know)? The case of Zulaikha is presented in such a way that the evidence is cleverly ambiguous and can be read either direction.

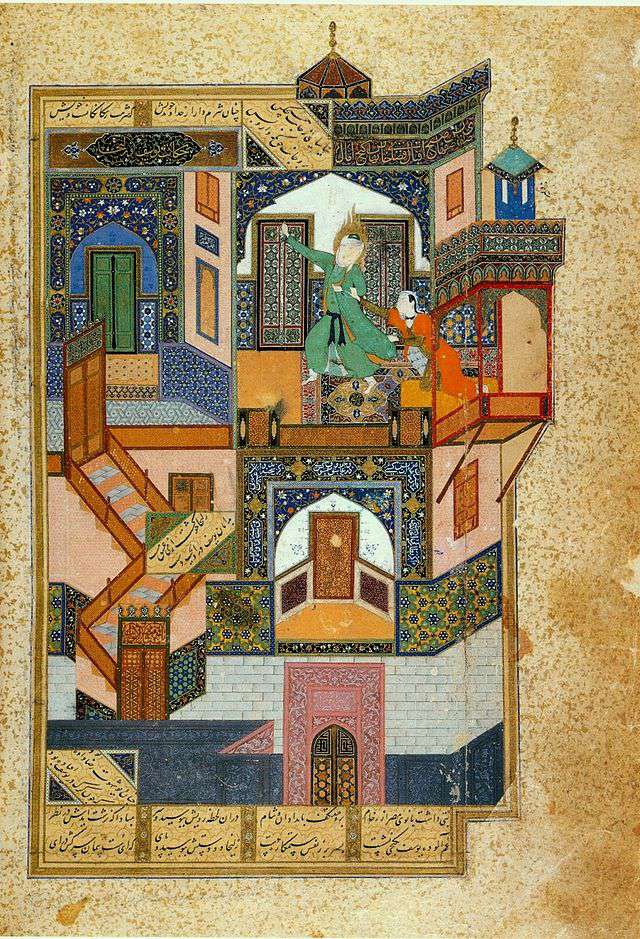

Zulaikha's love for Yusuf, according to the story tradition that culminates in Jami's famous account-- for a detailed discussion of this see {194,5}-- begins with a series of three prophetic dreams. These dreams lead her to marry the 'wrong' man, then to buy the slave who is the 'right' man; then she persecutes the slave for 'wrong' (erotic) reasons, and has him sent to prison (which is morally 'wrong', but also divinely 'right'). She then waits, humbly and passively, in a state of outer 'wrongness' and inner 'rightness': full of increasingly mystical love and suffering, she loses her health and even goes blind, and is widowed. When Yusuf is released from prison, he returns her now-pure love, and prays for her recovery; his prayer is granted, and they are married. Thus Jami's famous version of her story offers vivid examples of both headstrong, selfish, 'wrong' love, and mystical, sacrificial, 'right' love.

So if we want to consider the second line as offering a favorable example of the insightful power of (true? right?) love, then we read it as saying that a 'free gift', or even a 'trifle' (suggesting that much more significant gifts might also be available), given by the dream-linked surrender or submissiveness of Zulaikha is the power to move and flow like a fibrous stem, to 'run', to 'leap up' like a vine, and to 'graft' her affections into those of Yusuf.

And if we want to consider the second line as a counterexample, we can read it as saying that 'to run/flow/leap like a fiber/nerve/vein' [daviidan reshah saa;N] is foolishly aggressive, arrogant, inappropriate behavior; it's not the slow, quiet 'graft'-making that (true, proper) love would know how to do. Rather, it's a 'useless, unprofitable' effect of Zulaikha's initial headstrong rush to seduce Yusuf, and thus to claim the dream-created erotic passion to which she has long ago surrendered her life. For another verse about reshah-davaanii , see {184,3}.

It's a somewhat awkward-feeling verse, because the imagery is so abstract: it's hard to be sure of exactly what all the various elements of each line mean, and thus even harder to connect them in compelling and coherent ways. Maybe that's why Ghalib decided not to include it in his published divan.

For other, similarly abstract, uses of the 'dream of Zulaikha', compare {145,14 x} and of course {194,5}.

Asi:

Love knows the manner of the joining of the plant of friendship; that is, love is the kind of thing that knows the manner of the joining of the plant of friendship. For the 'dream of Zulaikha', to run and to flow like a fiber is entirely easy. That is, the effect of the vein of the 'dream of Zulaikha' reaches Yusuf. (238)