FWP:

SETS

== EK

DESERT: {3,1}

GRANDIOSITY: {5,3}

[SNIDE REMARKS ABOUT THE NATURAL WORLD, showing that it's derivative from or subordinate to the ghazal world:] {4,8x}; {5,4}; {15,16x}; {16,5}; {25,1}; {27,10x}; {38,2}; {62,8}; {68,5}*; {145,8x}; {178,2}; {199,5x}* // {312x,4}; {404x,3}; {405x,6}

For background see S. R. Faruqi's choices. For more on Ghalib's unpublished verses, see the discussion below.

Not just everything in the universe, but everything that is possible, everything imaginable, everything conceivable, becomes 'one' footprint. The use of ek to describe the footprint adds a further clever touch of multivalence (see the definition above): is the footprint single, or specific ('a certain'), or 'only' a footprint, or a 'unique' or 'excellent' footprint? To illustrate these affirmative possibilities of the ek , consider how elegantly Mir uses it in M{336,8}:

miir-o-mirzaa

rafii((-o-;xvaajah miir

kitne ek yih javaan hote hai;N

[Mir and Mirza Rafi' [Sauda] and Khvajah Mir

[Dard]--

how singular/unique/excellent these young men [habitually] are!]

In the present verse, no matter what kind of a footprint it is, we've left it behind; in a single step we're long gone, and what worlds, oh Lord, are left for us to conquer? (Maybe only the inner world of kindness and compassion for each other.)

The forceful internal rhyme of paa paayaa adds emphasis and a sense of impatience. Some critics have actually carped about it, considering its repetitiveness a 'defect' [((aib] and speculating that the awareness of this flaw is what caused Ghalib to omit it from the published divan. Among much other counter-evidence, a more than sufficient refutation of this view is found simply in the presence of {26,7} in the published divan.

The one thing I don't care for is the way the first line positions tamannaa kaa right before the quasi-caesura-- a place that almost forces extra stress, followed by a bit of a pause, in recitation. The effect is to give the line a thumping, overly broken-up quality (since the rhyming naa kaa sound-group is not only over-stressed, but also separated from the duusraa qadam with which it belongs and to which it should defer).

But what a phrase is dasht-e imkaa;N , 'desert of possibility'! Is it a 'desert' because it is full of redundant, useless, already-explored possibilities? Or is it a 'desert' of possibility in the sense that there is no possibility there? Or is it a 'desert' because we already know, even before exploring them, that in this world every possible possibility is finite, trivial, worthless, unhelpful? (Just the kind of questions, in fact, that we might ask about a 'desertful' of roses.)

Compare {102,1}, an almost equally extravagant verse that may (or may not) apply to God. And compare {93,3x}, the only other unpublished verse that's almost as famous-- and as brilliant-- as this one.

Compare also a verse of Mir's that picks up on the 'world of possibility' [M{715,7}]:

kahii;N ;Thaharne kii jaa

yaa;N nah dekhii mai;N ne miir

chaman me;N ((aalam-e imkaa;N ke jaise aab phiraa

[I didn't see anywhere here, a place to remain,

Mir

in the garden of the world of possibility, I wandered off like

water]

Mir also offers a much more sinister vision of

that first 'footstep', in M{745,6}.

Ghalib's unpublished early ghazals and verses are known to scholars from manuscripts that he compiled and presented to friends and patrons. It's astonishing that Ghalib left even a superb verse like the present one unpublished throughout his lifetime; he similarly neglected a number of other fine early verses (including the famous {322x,5}). When I used to discuss all this with Faruqi, he always pointed to it as a mystery. He finally gave it as his best guess that Ghalib felt that the verses that he had not initially selected for his divan wouldn't have added appreciably to his reputation, so he just never took the trouble to go back and pick them up later on. The largest group of these unpublished verses were from an 1816 manuscript, with an additional group collected in a manuscript from 1821. Mehr Farooqi and I have concluded that Ghalib's published divan should be seen basically as a 'selection', an inti;xaab , from his larger body of ghazals-- one of several such selections, with varying contents, that he made over the years.

It should also be kept in mind that Ghalib was never able to maintain a library of books or manuscripts, since many circumstances of his life-- his shifts from one house to another, his travels, his financial vicissitudes, the chaotic disruptions of 1857, even something like an unusually heavy rainy season (see {48,7})-- conspired against the orderly preservation of papers. So he might never have had a good occasion to sit down and seriously revisit the full set of his early unpublished verses; in fact he might not even have had convenient access to them at all, since the manuscripts we know of were mostly in the private libraries of some of his friends.

The crowning piece of evidence in this regard is a letter he wrote to his good friend Shiv Nara'in Aram on April 19, 1859: 'Sahib! From where would I send you Hindi [=Urdu] ghazals?! The printed Urdu divans are defective/incomplete [naaqi.s]. Many ghazals are not in it. The handwritten [qalamii] divans, which were perfect and complete [atamm-o-akmal], were looted [in 1857]'. (More of the letter is quoted in {178,1}.) Ghalib's own house was not looted, so the clear implication is that he did not have manuscripts of his early work in his possession. (For further evidence that this was the case, see the letter quoted in {26,1}.)

These few sentences also make it absolutely clear that as late as 1859, Ghalib considered the unpublished ghazals to be an integral part of his work, so that the printed divans that did not contain them were 'defective/incomplete'-- that is, were only a 'selection' [inti;xaab] made from the full body of his work. These few sentences are so decisively important that it will be worth looking at the exact text of the original: .saa;hib ! mai;N hindii ;Gazale;N bhejuu;N kahaa;N se ? urduu ke diivaan chhaape ke naaqi.s hai;N _ bahut ;Gazale;N us me;N nahii;N hai;N _ qalamii diivaan jo atamm-o-akmal the , vuh lu;T ga))e _ (Khaliq Anjum vol. 3, p. 1070; see {178,1}).

Many divan ghazals have unpublished verses. (That is, verses that were left unpublished by Ghalib himself; scholars have since collected and published them.) Whether or not commentary is provided on these unpublished verses, their texts are fully accessible: on any divan ghazal page, click on the 'full: Raza 1995' link and go to the page indicated, and you'll see the whole ghazal (according to Arshi's and Raza's best judgment); the verses not marked with a miim (for muravvaj ) are unpublished ones.

When such unpublished verses are among Faruqi's recommendations, I have provided commentary on them, marking the verse number with an asterisk (*). Beyond these, I have also added and commented on additional unpublished verses from divan ghazals-- ones that strike me as somehow interesting. 'Interesting' is of course a weasel word, and I'm using it as such; for more on my reasons for these additions, see {113,10x} and {143,9x}. I also once in a while include with a divan ghazal some formally identical unpublished verses recommended by Faruqi from a contemporary, entirely unpublished ghazal; these are always clearly identified as such. The most prominent and interesting such case is {145}; for a detailed discussion see {145,5x}.

For every divan ghazal that has unpublished verses, at least one or two of these unpublished verses receive commentary on this website. (This is partly just to make sure people know that they exist.) Isn't it striking to see Ghalib's creative processes at work-- to see something of the matrix from which the divan verses were selected? Here are the divan ghazals with unpublished verses for which all the unpublished verses in Raza's inventory have received commentary on this site: {03}; {04}; {06}; {09}; {12}; {16}; {18}; {25}; {27}; {33}; {34}; {37}; {39}; {42}; {51}; {57}; {61}; {64}; {68}; {72}; {77}; {78}; {80}; {84}; {85}; {95}; {100}; {108}; {109}; {118}; {121}; {123}; {131}; {132}; {138}; {139}; {140}; {141}; {150}; {154}; {169}; {186}; {189}; {192}; {193}; {196}; {206}; {210}; {211}; {212}; {217}; {223}; {230}.

There are also many entirely unpublished ghazals. The main 'ghazal index' page includes a separate index of all the entirely unpublished ghazals (that is, ghazals from which no verses appear in the divan), linked HERE; there's also an overview page for them. These ghazals are presented with full textual access through the Raza links and with access to commentary wherever possible, including commentary on this site. (There really isn't that much commentary available on them-- there's mainly Asi, and Gyan Chand, and the old but only recently published Zamin Kanturi commentary. I have commented on most of Faruqi's choices, and on some of my own as well. Here are the unpublished ghazals for which all the verses in Raza's inventory have received commentary on this site: {241x}; {280x}; {307x}; {314x}; {320x}; {321x}; {322x}; {323x}; {351x}; {352x}; {353x}; {360x}; {361x}; {398x}; {404x}; {413x}; {417x}; {423x}; {424x}.

Scholars, please note: There are many textual complexities and choices involved in assembling any list of the unpublished ghazals and verses. I am *not* going to enter the labyrinth of the various manuscripts, with their variants, their marginal annotations, their discrepancies over time, etc. About, say, eighty or ninety percent of the unpublished verses can be presented with confidence; but the remaining ones are a quagmire. By using Raza 1995 (a very defensible choice), I am resolutely skating over the surface of this quagmire. Ars longa, vita brevis. Mehr Farooqi's Ghalib: A Wilderness at My Doorstep: A Critical Biography offers the best available account of the textual history of Ghalib's ghazals.

Later critics have often claimed that Ghalib repudiated his unpublished early verses. As an example of such views, consider Azad's highly tendentious and unreliable account provided above; it's full of his sly, dexterously anti-Ghalib insinuations. But even Azad's account twice refers to Ghalib's divan as a 'selection', an inti;xaab . And of course, the making of such a 'selection' doesn't necessarily show any rejection or repudiation of the verses not included in it. (If some texts are chosen for some particular purpose, does that mean that those not chosen are disdained or rejected?) Moreover, such 'selections', like anthologies, were often based upon particular qualities (e.g., simplicity, immediacy of effect, desirability to a patron) that were meant to appeal to certain (kinds of) readers, rather than upon genuine personal preference or literary judgment.

In the Persian preface to the first published edition of his Urdu divan (1841) Ghalib included the following ornate disclaimer: 'It is hoped that the poetry-composing poet-praisers, finding scattered [paraagandah] verses outside of these pages, would not consider them to have been blackened by the scratching of the vein of the pen of this treatise, and would not think the poem-gatherer [=Ghalib] to be honored by praise, or reproached by blame, concerning those verses' (text given in Raza 1995, pp. 87-88; trans. by Owen Cornwall, July 2014). This disclaimer is one of the two pieces of evidence often cited to show that Ghalib rejected his own unpublished ghazals and verses; but in it Ghalib does not say or imply that he himself had composed the verses he so firmly repudiates.

In fact this elaborate caveat seems most probably to be aimed at the vexatious presence of other poets' verses that were either ignorantly, or satirically, or teasingly ascribed to Ghalib; such false ascriptions so annoyed him that he was driven to obscene abuse of the perpetrators (for discussion, see {219,1}). For examples of how fake verses were satirically ascribed to Ghalib by other poets, see 'The Meaning of the Meaningless Verses', pp. 264-266. There's a lot to be said on this subject; but certainly in 1828, when he was in the process of choosing verses for his divan, Ghalib was very far from repudiating what are now the unpublished verses, as can be seen from the many unpublished verses included in his other early 'selection' from the same year, the manuscript collection Gul-e ra'na.

The only other piece of relevant evidence I know of is the letter translated and discussed in {155,3}. It's a very tendentious letter, and contains several obvious, manifest, provable falsehoods. So it's an extremely weak reed on which to lean. But 'natural poetry' fans are rarely put off by weak evidence; many of them would rather dismiss Ghalib's complexities than seriously engage with them. In any case, we will almost certainly never be able to know exactly how Ghalib decided how many verses, and which ones, to include in his published divan.

For an example of some late verses that Ghalib clearly did want to have included in his divan, but that at the end of his life remained unpublished, see {216,1}. (Such genuine verses are NOT to be confused with apocryphal verses wrongly attributed to Ghalib; for discussion of these, see {219,1}.)

Sometime I'd like to go into this whole question in much more detail. In the meantime, please note that this present ghazal, {04}, is itself quite early (1821), and surely it can't reasonably be called anything other than simple and straightforward. (For one interesting thematic comparison, juxtapose the very early unpublished {223,6x} to the late {98,10}.)

When C. M. Naim, my teacher, founded the Annual of Urdu Studies, he chose this

particular unpublished verse as the sole adornment of the cover

of every single issue. I think it was worthy of the honor. Just

for pleasure and nostalgia, here's what the covers looked like:

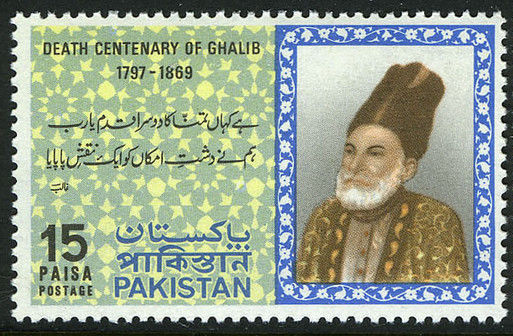

This verse was also chosen to appear on a 1969 Pakistani commemorative stamp:

Azad:

There is no doubt that through the power of his name [since 'Asad' means 'lion'] he was a lion of the thickets of themes and meanings. Two things have a special connection with his style. The first is that 'meaning-creation' and 'delicate thought' were his special pursuit. The second is that because he had more practice in Persian, and a long connection with it, he used to put a number of words into constructions in ways in which they are not spoken. #496# But those verses that turned out clear and lucid are beyond compare.

People of wit did not cease from their satirical barbs. Thus one time Mirza had gone to a mushairah. Hakim Agha Jan Aish was a lively-natured and vivacious person.... He recited this verse-set in the ghazal pattern:

For this reason, toward the end of his life he absolutely renounced the path of 'delicate thought'. Thus if you look, the ghazals of the last period are quite clear and lucid. The state of both [earlier and later poetry], whatever it may be, will become apparent.

From elderly and reliable #497# people I have learned that in reality his divan was very large. This is only a selection [inti;xaab]. Maulvi Fazl-e Haq, who was unequalled in his learning, at one time was the Chief Reader of the court of Delhi district. At that time Mirza Khan, known as Mirza Khani, was the chief of police of the city. He was a pupil of Mirza Qatil. He wrote good poetry and prose in Persian. In short, these two accomplished ones were the intimate friends of Mirza Sahib. They constantly met together in a friendly way and discussed poetry. They heard a number of ghazals [of Ghalib's]. And when they saw the divan, they persuaded Mirza Sahib that these verses could not be understood by ordinary people. Mirza said, 'I've already composed all this much. Now what remedy can there be?' They said, 'Well, what has been done has been done. Make a selection, and take out the difficult verses.' Mirza Sahib gave the divan into their care. Both gentlemen looked it over and made a selection. That is the very divan that we today go around carrying pressed to our eyes like spectacles!

==this trans: Pritchett and Faruqi, Ab-e hayat, pp. 405-06 (slightly edited)

==Azad, aab-e ;hayaat , pp 495-497