FWP:

SETS == WORDPLAY

COMMERCE: {3,3}

DREAMS: {3,3}

For background see S. R. Faruqi's choices. This verse is NOT one of his choices; I thought it was interesting and have added it myself. For more on Ghalib's unpublished verses, see the discussion in {4,8x}.

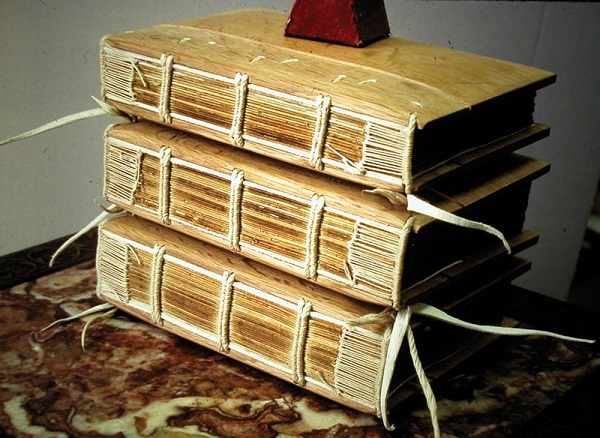

On the shiiraazah and book-binding technology, see {10,12}.

Asi here reveals one of the weaknesses of the 'natural poetry' approach: if a verse is basically to be equated with its prose meaning, then a commentator can say disdainfully, as Asi does, 'I don't understand whether this is a verse, or a medical prescription'. Let's help him out here: it's a verse. No medical prescription would analogize a 'vein of sleep' to a 'binding-thread', and then go on to muster an enjoyable network of imagery from the world of book-making and account-keeping: .sarf , shiiraazah , daftar , rab:t , dar-ham .

Moreover, the verse praises sleep in a far more heartfelt, existential way than any medical prescription could match. It reminds me of Macbeth's similar praise in Act II, Scene 2, of 'innocent sleep'-- which comes just when he feels that such sleep has abandoned him forever:

Sleep that knits up the raveled sleave of care,

The death of each day's life, sore labor's bath,

Balm of hurt minds, great nature's second course,

Chief nourisher in life's feast.

But even more to the point, the verse may not be as much about sleep, as about dreams. Are our lives not held together by our dreams, our sleep, our inner visions? Is this not true in a much deeper sense than the simple medical one?

Compare the gorgeous {10,12}, in which the 'binding-thread' is not the rag-e ;xvaab , but the gaze.

Asi:

If the vein of sleep would not keep acting as a binding-thread for the signatures [ajzaa] of the temperament, then all the record-books of the temperament would become jumbled and defective-- that is, the temperament would be destroyed. According to the principles of medicine [:tibb], if sleep is ruined, an alteration in the personality takes place. This is correct, but I don't understand whether this is a verse, or a medical prescription.

== Asi, p. 296