FWP:

For background see S. R. Faruqi's choices. This verse is NOT one of his choices; I thought it was interesting and have added it myself.For more on Ghalib's unpublished verses, see the discussion in {4,8x}.

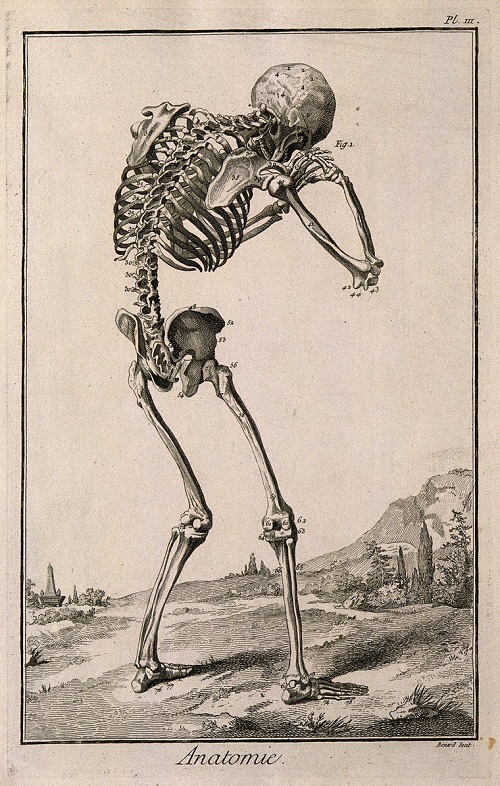

We can be sure that if the bent back of old age resembles a 'mischievous' eyebrow, the eyebrow can only be that of the beloved. What other eyebrow would the lover ever even notice, much less care enough about to use it in a metaphor? It's also possible that when the beloved sees his bent back, she then gestures to him by means of a raised eyebrow.

In either case, the 'mischievousness' of the eyebrow-lifting gesture lies in its ambiguity. What does her raised eyebrow mean? Does it show surprise (that what's-his-name is still around)? Does it hint that she is paying special attention, and will deal with him later? Does it show displeasure (since it's high time for him to leave the field)? Does it suggest that she might finally be ready to finish him off (as he longs for her to do)? In any case, Zamin is surely wrong to condemn the sho;xii as mere 'padding'.

'Natural poetry' fans should note that when Ghalib composed this seemingly personal 'old-age' verse, he was something like twenty years old. More such examples: {85,8}. For more on the problems of 'natural poetry' readings, see {66,1}.

For a truly brilliant use of the bent-back image, see Mir's M{17,8}.

Zamin:

That is, the bent stature, which has the similitude of an eyebrow. From it the suggestion is created, 'Now go along!'. The word 'mischievousness' is entirely for padding, and is inappropriate!

== Zamin, p. 341